Process

Although I’ve designed many games prior to this one, this project had a number of “firsts” for me. It was my first game based on a licensed IP, it was my first design where I was specifically hired by a publisher to do a design, and it was my first with a deadline--and a short one at that, which would make it the quickest design I had ever done.

The timeframe was the biggest thing I was worried about when I took this on, but in the end it was a blessing. It forced me to focus, playtest earlier and harder than I usually do, and make tough choices. I have a tendency to “theory-design” in my head quite a bit before testing, to try to identify problems and strategies. It’s a bad habit. There’s really no substitute for testing a physical prototype.

For my day job I do engineering product development, and hitting milestones is a key part of being a professional, and not just a tinkerer. Having a deadline to complete a design really forced me to professionalize my process, set intermediate goals, and all the good things you should do on a project.

I’m a big believer in constraints aiding the creative process, and The Expanse reconfirmed my thoughts on that. I was given a specific set of criteria by WizKids: theme, component cost, complexity, play time, and when I needed to deliver. I’ve never designed like that before, except perhaps for Survive: Space Attack, but that was an extension of an existing game. My other original designs were all clean sheets of paper, and I could go in any direction I wanted, which makes it harder to settle on a final direction.

Theory

I’m a big fan of The Expanse universe, and had a good idea of what I wanted to achieve. It’s very much about political maneuvering and posturing. While the threat of war is ever-present, war really doesn’t break out--at least not in the part of the series that was going to be covered by the game.

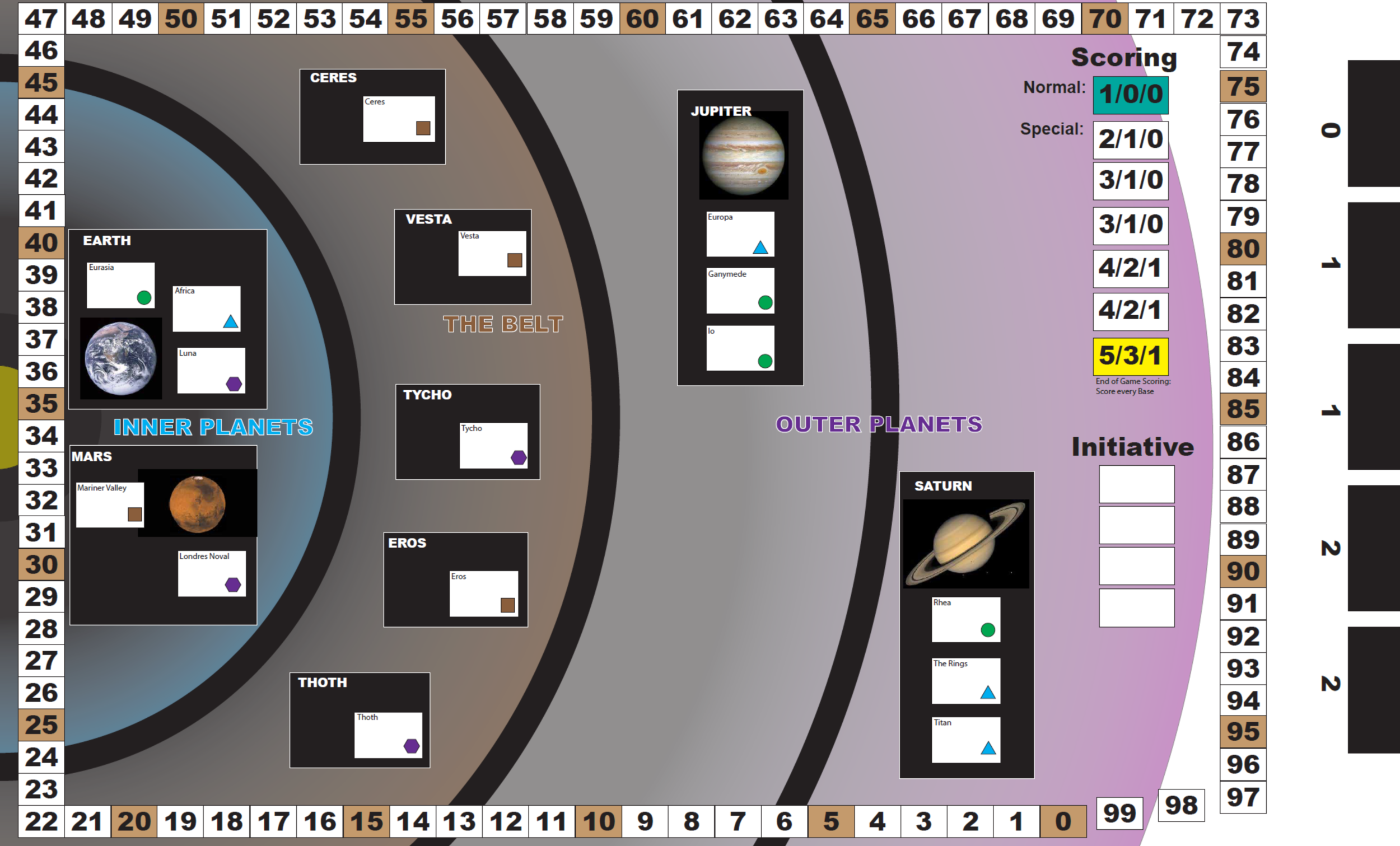

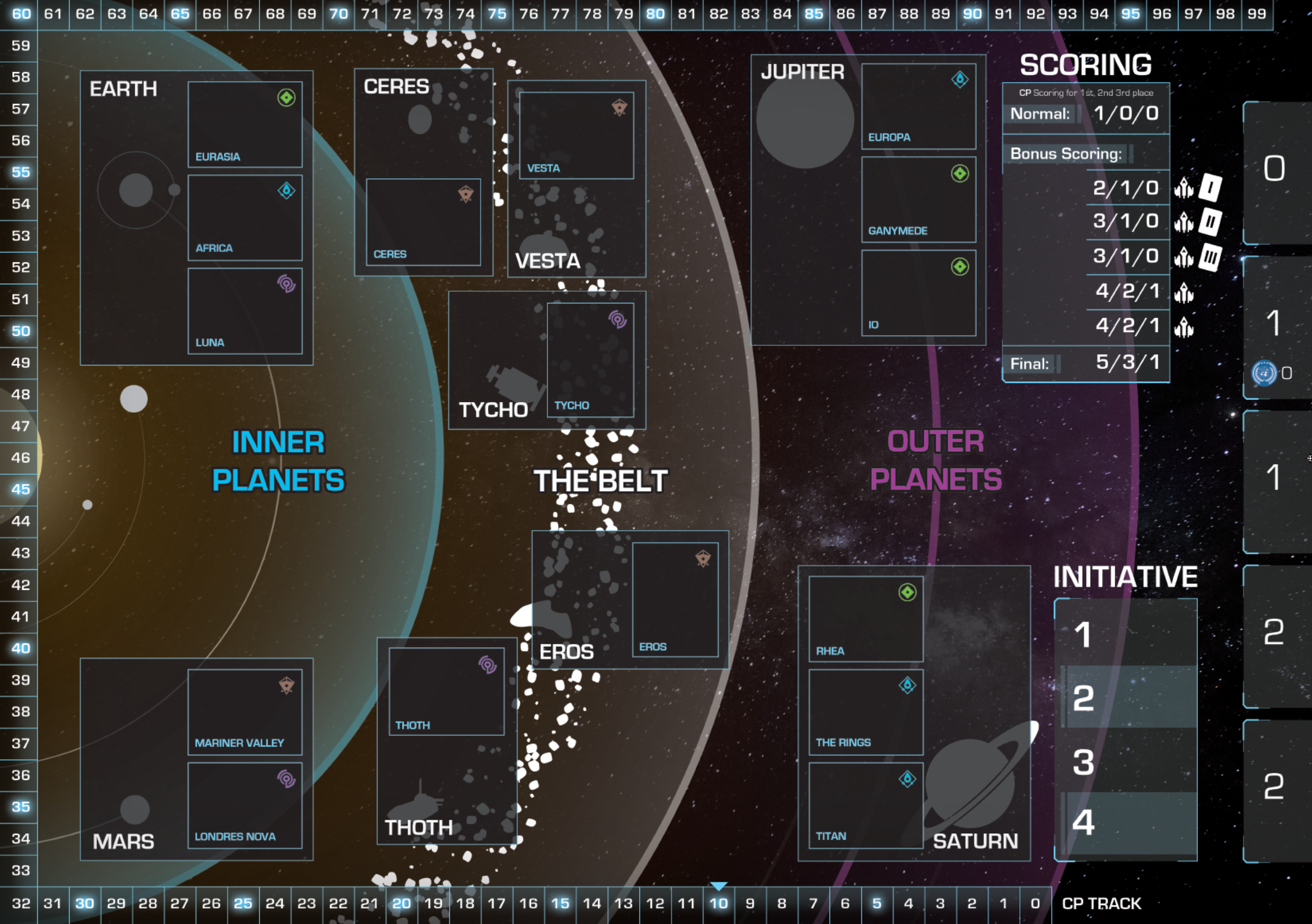

So, in spite of all the military deployments in the source material, a “dudes on a map” game like Kemet or Twilight Imperium really wasn’t going to work. It also wouldn’t fit the type of components WizKids wanted to use for this project. But the scope needed to be big, as the desire was for the players to represent the big factions in the game, not individual characters having adventures.

The key feeling I wanted to capture was one of spreading influence and pressure, which naturally translated into an area control game.

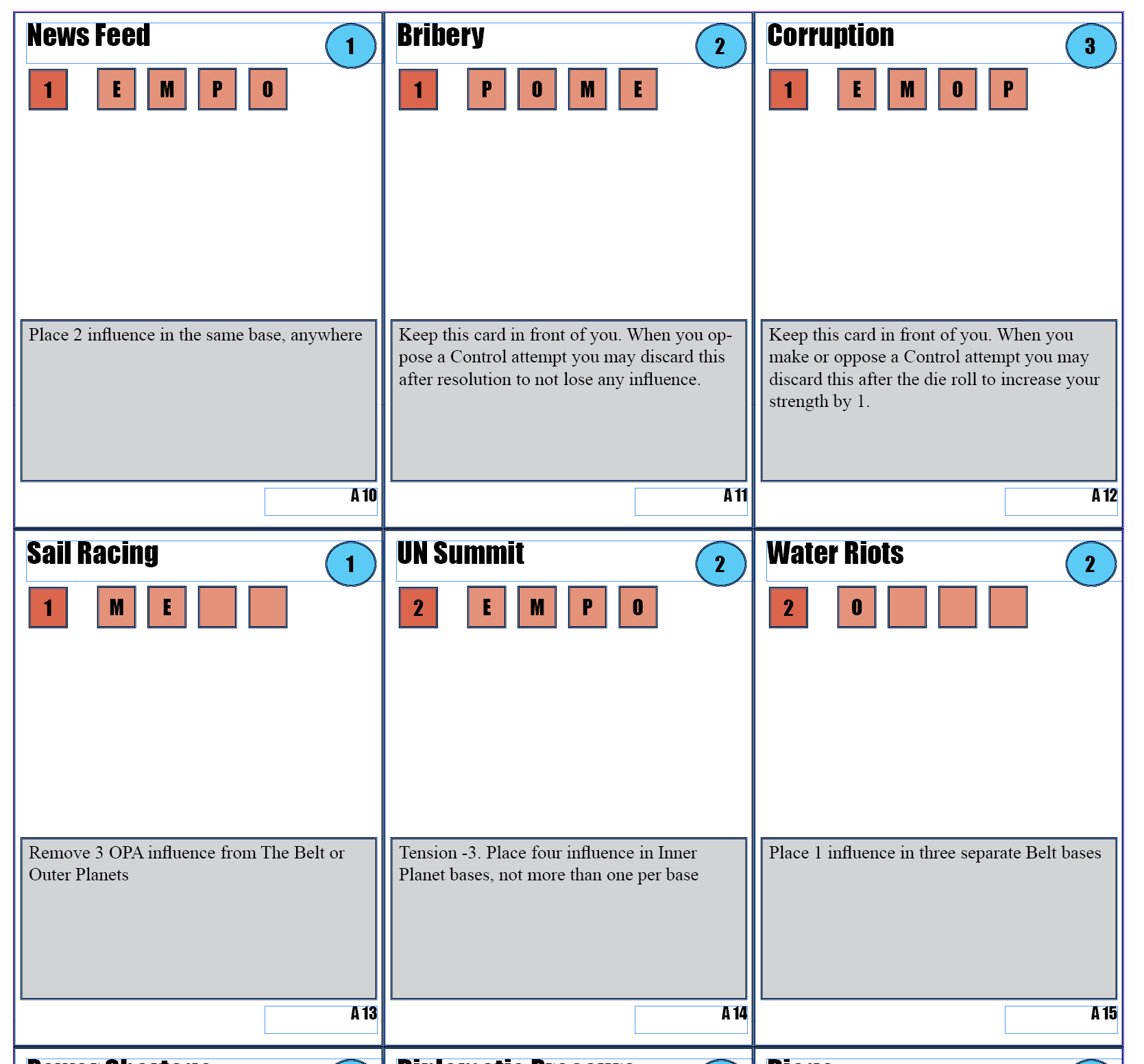

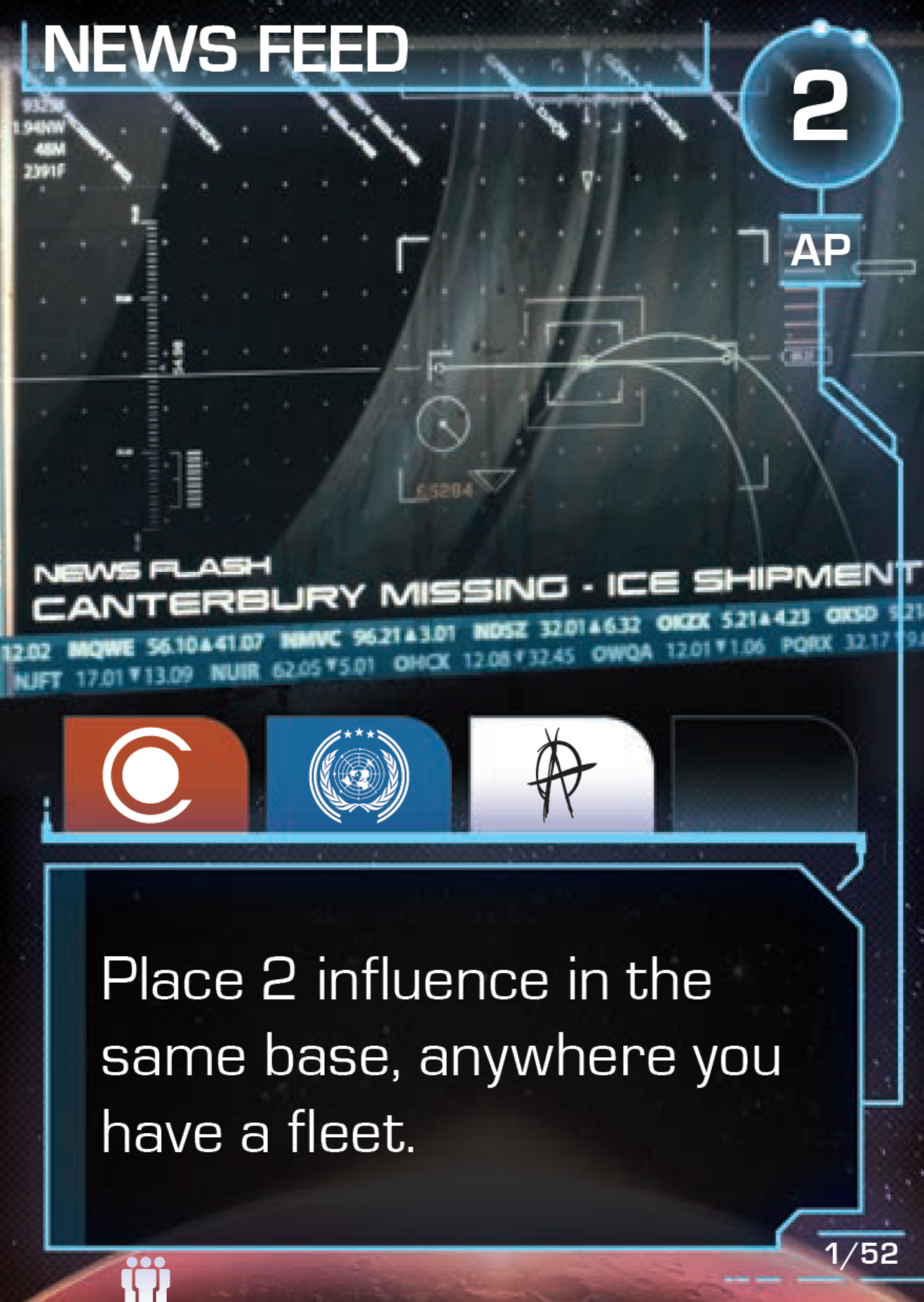

My main inspirations were the dual-use cards of Twilight Struggle and the COIN series, where other players might get to do actions based on cards played on your turn. As is my wont, I started too big, with too many options and mechanics. For example, originally every faction had different goals to win the game, there was an economic system, and there was a whole “tension” mechanic that governed what players were allowed to do.

These proved to push the game past the complexity we wanted for the target audience, and in any case didn’t really add that much interest. I ended up differentiating the factions by giving each a series of special abilities (called Techs) that are gradually introduced throughout the game. This controlled the complexity, by slowly introducing special abilities, but also recreated the tension mechanic by making it easier for players to attack each other as the game went on.

The biggest design challenge was making the Action/Event system work for multiple players. If the active player couldn’t or didn’t want to do the event on the card, who would get to do it? In the end, simplicity won out, with a basic priority system that added interesting choices, layered on top of a “card queue” system. The economic system got absorbed into the Victory Point system. Rather than adding a new resource into the game, players can spend VPs to do special things, and controlling bases that match the type of resource they need (like Food for the OPA), gives bonus VPs, which gives more spending flexibility.