Theory

My company, Smirk & Dagger Games, is well-known for its design aesthetic, in that we specialize in “stab your buddy” games. I just think they are more fun--highly emotional, laugh-filled, curse-filled, fun.

Every aspect of Cutthroat Caverns was carefully designed to live up to that and was inspired by my early years of playing Dungeons & Dragons. You see, my high school D&D group was very Tolkien-esque. We were all pretty Lawful Good, “all for one, one for all” brothers in arms. (Actually, my 1980’s player group was entirely women, other than me, but that’s beside the point.) If you found a magical item, you gave it to the person who could best wield it. We were all true heroes.

Well, when I got to college and played the first time with a whole new group, it was quite different. Chaotic Evil alignments, selfish unscrupulous folk, assassins, true mercenary brutes, all of them. I shall never forget the horrifying moment that I suddenly realized that the other players in my party were far more dangerous than any creature the DM could summon. That feeling of shock and horror was the exactly what I wanted to recreate and perpetuate throughout Cutthroat Caverns.

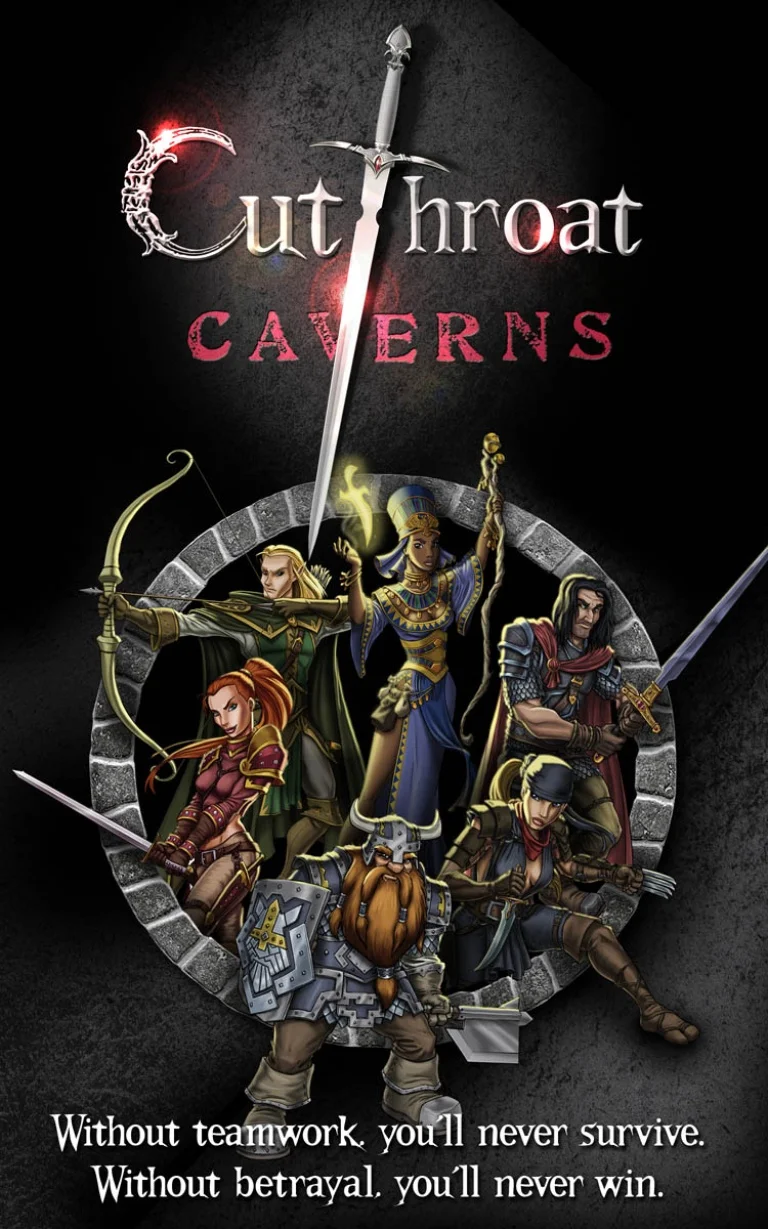

So I started with the premise. You’re a group of adventurers who had vowed, by all you hold sacred, that each day the first pick of treasure would go to the person with the most prestigious kills--except today, you found “the one ring / the holy grail / the most glorious treasure imaginable” and now you will do anything to make sure that person is you. But this is a vicious dungeon, filled with creatures that will overwhelm and destroy you, and you must escape before you can claim your prize. As the box says, “Without Teamwork you’ll never survive. Without Betrayal, you’ll never win.” It is a game about “kill stealing” and gaining more prestige by landing more killing blows on the toughest creatures--before the other party members can. It was a simple enough construct--but lead to a pretty unique style of game play. Too diabolical to be called a semi co-op, I coined the term “cooperative backstabbing.”

The monsters in the game had to be deadly and the illustrations and mood of the game had to put players on the defensive. Each time an Encounter is revealed, there has to be a gasp around the table--an ‘oh, crap!’ moment, in which they fear for their lives. That perpetual feeling becomes the driving force to work together. Then, balanced in equal measure, each creature also provides a reward for your sudden and inevitable betrayal.

It was clear that the creature stats would need to increase with the number of players at the table, in order to keep the threat level appropriate. But I took this opportunity to assure that the player elimination aspect of the game, which can be polarizing for players, didn’t lead to anyone being pushed out too soon. I simply ruled that, should players die early on, the creatures you’ve yet to face would not get weaker. The creature stats remain set to the number of people who started the game and the remaining players may no longer have enough firepower to win. This encourages keeping your opponents alive in the first three quarters of the game, yet allows for player elimination in the end game, especially of the prestige leaders, to remain an important avenue for players to win.

I then turned my focus to the players and the core mechanics of the game. For thematic reasons, I didn’t want any straight-up, player-versus-player combat. After all, we are a team--right, Boromir? Instead, player conflict would be more passive aggressive, as you attempt to get other players hit more often by the monsters. I also decided, at the outset, that there would be no dice rolling in the game, especially in regards to combat. Those games already existed and I was hunting for a different experience. But more important, I wanted players to have a high degree of control over how hard or soft they would strike. I wanted an intricate dance as they jockeyed for position to land the killing blow. Borrowing initiative order from my days of D&D, players would know and could plan their strategy in secret based on turn order, but would have to “set” their selected attack without knowing how hard others would swing.

I was delighted to discover that cards doing little or no damage could be just as valuable as those doing a lot of damage. If you can’t kill the creature yourself this turn, your best play is to sandbag, hoping the creature survives long enough for you to kill it next round. Most players assume low cards are worthless and watching their faces light up as they discover their value is almost as sweet as watching the faces of those who feel robbed of a kill, because they had planned on you doing more damage. I love to see people discard low cards, knowing they still have much to learn about the game.

Of course, there needed to be “take that” cards capable of increasing or decreasing your attack strength, changing initiative, spoiling your attack completely, stealing items or reassigning damage as well as limited-use items to fight over, which never get shuffled back into the deck, to keep their intrinsic value high.

There were two design decisions that were long debated, Bonus Prestige and Character Abilities. One concern, early in design, was the emergence of a “runaway leader.” At some point, it could be mathematically impossible to catch up with the leader, and this drains the fun out of the endgame. One solution is for players to eliminate the leader or several of them at the end of the game, but this is not always possible. So I devised a somewhat controversial fix, Bonus Prestige. In Rounds 7 and 8, as the exit draws closer and the tension rises, creatures deliver 3 additional bonus prestige. In rounds 9+, five bonus prestige are added. This provides those trailing in prestige a means to catch up in the critical last rounds. It is an effective solution, but has been criticized by some who felt the first encounters mean almost nothing, so long as you score the final kill. In truth, it isn’t quite so, but it most certainly can make all the difference. But I could find no better solution at the time. Since then, additional prestige resources (Relics, for example) have mitigated this.

The second debated design consideration, perhaps the most hotly fought in development, was whether or not we should have asymmetrical characters in the game, granting players unique abilities. With the creatures changing the play environment every round, with different rules and exceptions, I felt strongly that player abilities would only further complicate the game. Worse, I was afraid that players would argue about the balance of the character abilities. I never wanted to hear, “If I’m not the Dwarf, I’m not playing. That’s the only way to win.” Instead, I wanted the sole focus of the game to be about the players themselves and what they were willing to do to each other to win. That was far more interesting and engaging game play, a social experiment almost. But my partner argued that when you play a fantasy adventure game, players want and expect that their characters will be unique. We were both 100% correct. I made the final call to go without. It was more important to deliver a game unique unto itself.

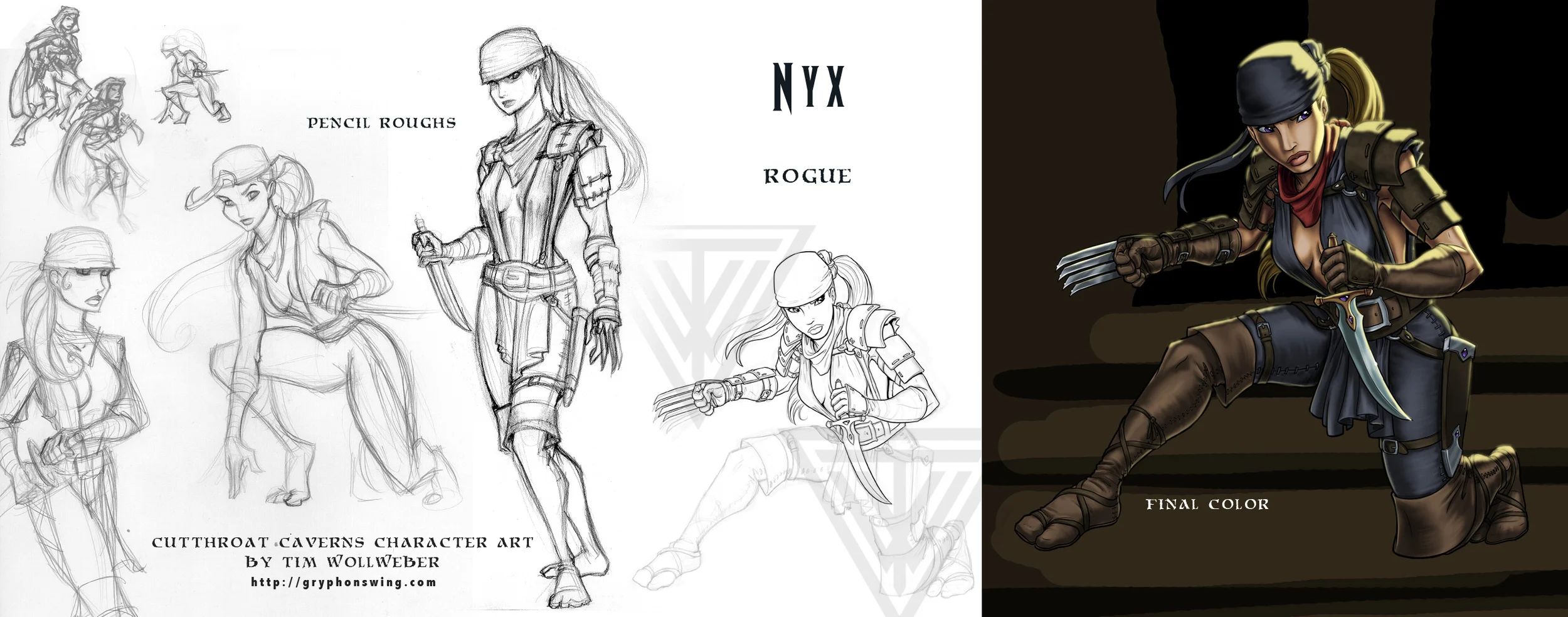

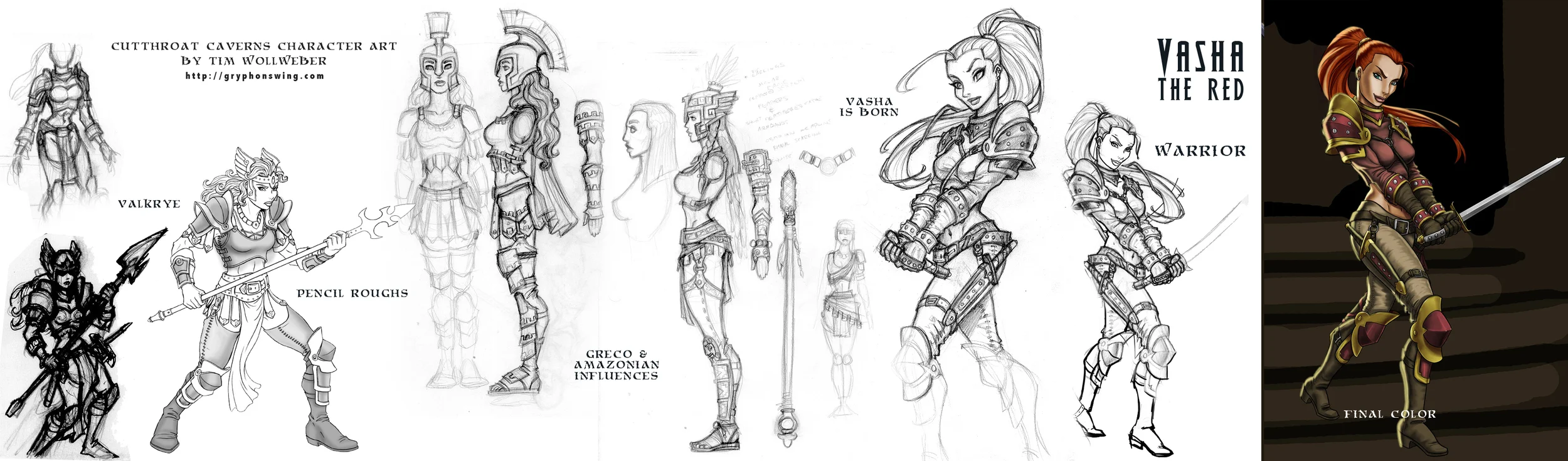

But fans echoed my partner’s position. In the first expansion, I tried a limited one-use ability to try and meet their demands, but I was never happy with it. Years later, with the concept of drafting more popular, I finally found a great solution. I allowed players to draft ability cards and then choose abilities they wanted before the game began. But for each they took, their maximum Life Totals would be decreased. The fact that they could construct their own characters removed the possibility of arguments over balance. In addition, we created 12 pre-set characters, should players want to play them, which were created from the ability cards used in the draft, theming the official characters of the game. I’ve been very pleased with how it came out.

In truth, the “tool kit” of mechanics and variables in Cutthroat Caverns are fairly limited and straightforward. And it is therefore shocking how much variety we have been able to deliver, in terms of unique encounters (of which there are now 140 or so), items and events. Each encounter drips with theme and plays very differently from one another. This variety, and the emotional impact the game delivers, is what brings people back, time and time again. I think it remains my best design.

The Takeaway: Create a glossary for your game at the outset, and live by it religiously. I’ve had a very rough learning curve on this with Cutthroat. Synonyms, alternate phrasings, inconsistent descriptions can all lead gamers to infer unique rules loopholes, where you intended none, or else lead to needless confusion. I’m sad to say, the game still suffers a bit from my sins of the past in this regard, but I’ve learned a valuable lesson for the future.

Without engaging the emotions during the game, there is no story to tell after the game. Epic betrayals, clutch plays, triumphant comes-from-behind--this is the stuff of legends. Playing your game should lead to great tales.

I love the delicate balance of cooperation and betrayal needed to win. There is such an amazing dynamic here and one I would love to see explored more in the industry.

The best designs allow your fans to contribute to the game. After our first expansion, I wanted to deepen the relationship with fans and their involvement in the game--just as I had done so many years ago building expanded content for games I loved. In Deeper & Darker, I included a surrogate encounter card that would be a placeholder in the deck for your own creature designs. A year later, I ran a contest to create a new encounter for the game. The winner would have their encounter considered for inclusion in our next expansion and they’d win a bunch of games from our catalog. Well, I was bowled over by the response. I thought I might get a few very rough ideas. What I got was almost a hundred well-considered encounters, which pushed the game into lots of new and innovative directions. Sure, we had plenty of work to do to balance and refine them, but it inspired and created game content for our next two expansions, including the Event deck of Relics & Ruin, and a slew of brilliant creatures like fan faves, WereBoar, Gluttony, Greed and Emperor Lich.

I learned the power of creating a “funnel” in the game. Since I wanted a specific emotional reaction consistently throughout the game, I had to define it and then find almost endless ways to elicit it with a handful of game tools--imminent death versus a host of possible rewards for risking the death of yourself and everyone else. Anything that helped funnel people towards making this critical decision was exploited and added to the game. Anything that did not was cast aside.