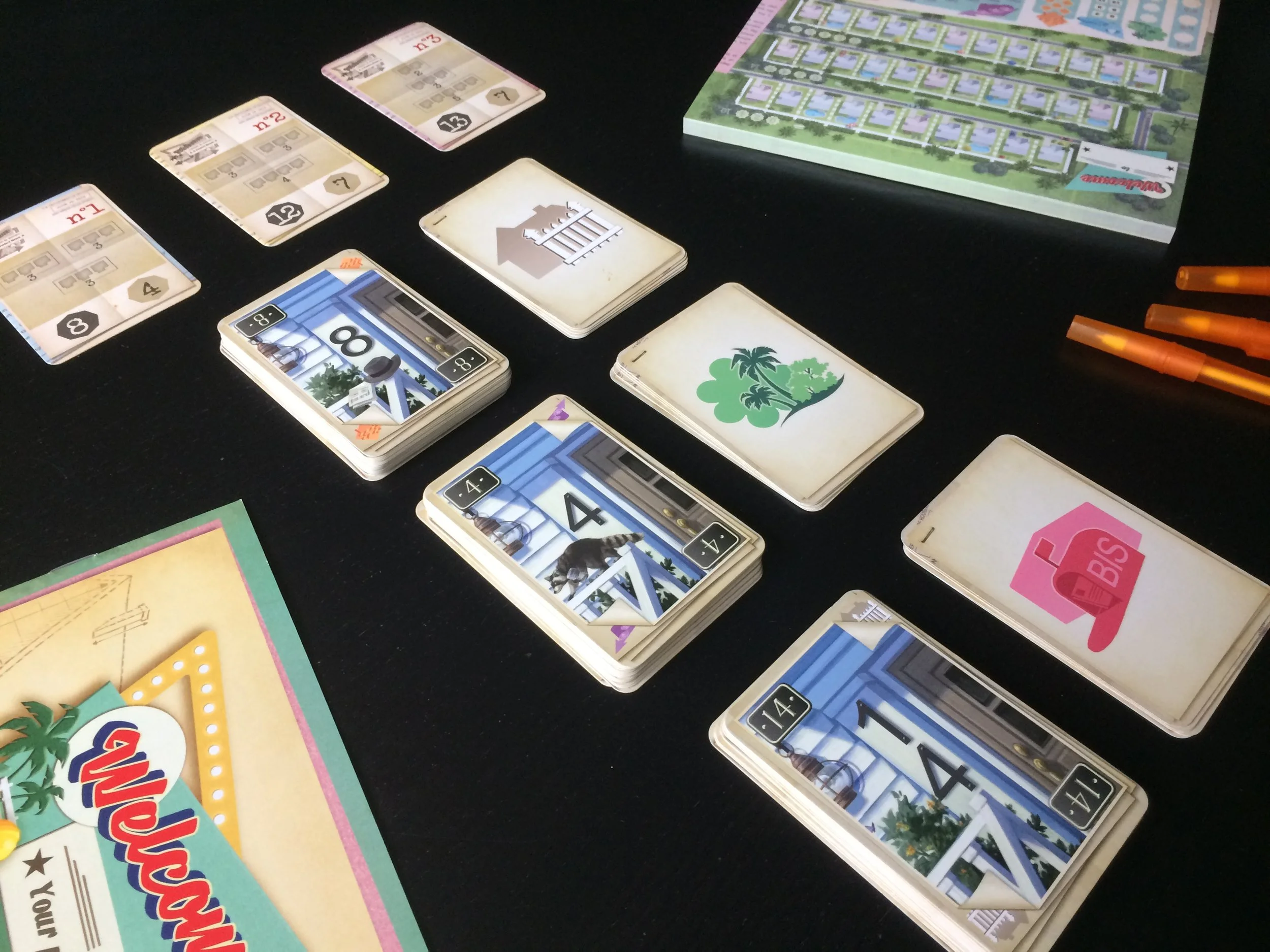

Welcome To... is often grouped together with roll-and-write games despite the fact that it doesn't have any dice. Instead, the game uses a deck of cards to control the random output from which players select their actions each round. Was this core system always the same, or did it change during development?

Actually, not at all. The core system was originally dice-based. You had three custom D8 dice with a color and a number on each side. You rolled the three dice and then combined them two-by-two, numerically and chromatically. For example, you would get a 2 blue and a 3 yellow, and that would make a 5 green. So you had, in the end, three combinations with numbers ranging 1 to 16 and six different colors corresponding to the six effects. That was the system I came up with, with the express desire to make a game system as pure and elegant as can be. Three dice and nothing more; but lots of possibilities. So at its core, Welcome to... is definitely a roll-and-write.

However, during the development phase, two things came up: One, the game length was too long. Around 40 to 45 minutes a game. And a good chunk of the game was dedicated to figuring out the three combinations each turn (six mathematical operations every time). And one of our playtesters (a local store owner) felt that the game was not a dice game in the sense that the player rolling the dice had no benefit compared to the other players. He was just “the Randomizer” (a cool title but still...).

So we went on looking for a better way to randomize the results (after a brief but painful phase where I had to say goodbye to the basic principle of my game--a necessary evil and a good lesson for a new game designer like me, but ouch...). The first goal was to replicate purely the dice roll without any dice. And we tried many things, from tokens pulled out of a bag, tokens dropped on a board, and many variations of card dealing. It was not easy to replicate the breadth of possible combinations without having an insane amount of components or a very clunky interface. But when we tried the card system present in the final game, we knew we had found the solution. Having the combination created by pairing the different sides of the cards allowed both the replication of the dice randomizer to a T, and got rid of the lengthy math phase. Suddenly, the game was 15-20 minutes shorter.

And from there, new options came: altering the gaussian bell curve to better fit the flow of the game; adding the effect on the top part of the number side to give player a bit more info to make their decision; and also, quite naturally, give the players a sense of control to the randomness. So, even though this “better control of the randomness” is often hailed by reviewers as a key part of the game system, it is just a byproduct of a completely different game design issue… And from my perspective, controlling randomness is important but not always a good thing...

Are there things that designers of roll-and-write games (or flip-and-fill games, as Welcome To… has been called) can or should do to mitigate randomness and give players more predictability or control?

In a roll-and-write, randomness is structurally a factor players have to take into account. Sure, there is a wide range of randomness from Yahtzee to La Granja: No Siesta, but if there is no randomness, then it is not a roll-and-write. It becomes a very different type of game, more akin to worker placement or action selection than R&W. So mitigating randomness should not be the ultimate goal when designing a R&W. For example, in Welcome To..., players can know the distribution of the cards, and can do a bit of card counting, but we limited this control by allowing at least one reshuffle of the deck during a game. Why? Because if players had access to complete information, then AP (analysis paralysis) could set in, and the game would just be a solvable, dry math problem. And that’s no fun… (at least for me).

So “things designers can or should do to mitigate randomness” are two very different questions...

Should they do it depends on the kind of experience they want to create. For example, Avenue has more randomness than Welcome To... and it gives a very different feeling: more highs and more lows because players are less in control, so they enjoy more having a break (feeling lucky is feeling good) and whine more (or is it just me?) when the fourth golden card comes too soon. And it is not a problem at all. It makes the game more accessible thanks to the lack of mitigating mechanics. It also can make games meaner, in Qwinto most notably. In Qwinto, the design is so sparse that there is very little luck-mitigating elements. And it can feel brutal sometimes. But this feeling is also explained by the type of randomness involved in these games.

Qwinto and Welcome To... share some similarities (most notably the three lines of ascending numbers) but the type of randomness in these games are very different. Qwinto has what is called output randomness: players make a decision (roll one, two or three dice) and then the die roll gives a random result and players have to deal with it. The designer mitigated the randomness using two tactics: First, by allowing the players to choose which die to roll, he gave the players control of the bet they were making. And then, the players can reroll if the result isn’t satisfying. But as you made your decision beforehand, the stakes are very high with each roll.

In Welcome To..., there is rather input randomness: players are randomly dealt three choices beforehand, and then they decide what to do with it. This type of randomness gives the player a bigger sense of control (it’s the same one you get in euro-style games; whereas output randomness is more akin to “ameritrash”). You pretty much always have the opportunity to adjust your strategy to the random result, and you get a feeling of “building something” more coherent. But at the same time, you won’t quite get the thrill of rolling the perfect number after sticking to your bet. You do get a bit of it, bingo-style, waiting for the 10-pool you so desperately need, but the stakes are lower.

So “should” is very much a design philosophy, and many great games went opposite routes on that.

As for “can,” designers have a very large panel of options. The most frequent design strategies are allowing the players to re-roll, allowing some players (usually the passive players in R&W) to refuse using the results; and giving several options to pick from the random result: In Ganz schön clever, for example, as the active player, you get to reroll and pick from several dice.

Designers can also use modifiers, powers that allow the player to manipulate the result of the die roll (+1 to a die, turning a die on its opposite side, etc.). For cards, Welcome To... uses a system where players know the effects of the next turn, but not the numbers, so that they can form a bet, akin to the dice selection in Qwinto. In Roll to the Top!, the designer used another system where players can adjust the random factor of the die by picking a different die, from a D4 to a D20, forcing the players to choose between safety and potential high rewards, which is pretty smart.

But personally, one of the best ways to mitigate the randomness is not by controlling the die roll or card flip, but rather by giving the players decisions to make after the random result. What I mean is that if the only thing to mitigate the luck you have is to act on the die roll, you will feel pretty helpless once you used all your tricks (rerolls, modifiers, etc.) if you have only one place to put your result in. Just imagine playing Qwixx by rolling one white die and one colored die (that you chose). You would feel very dependent to the randomness. As soon as you give players options on the result (which dice to use in Qwixx, which line to write your number in Qwinto, which route you connect in Avenue), then not only do you mitigate the luck, but you give the players a feeling of control over their game. And the best games are those where this decision is crucial because whatever you do, you always give something up in the process.