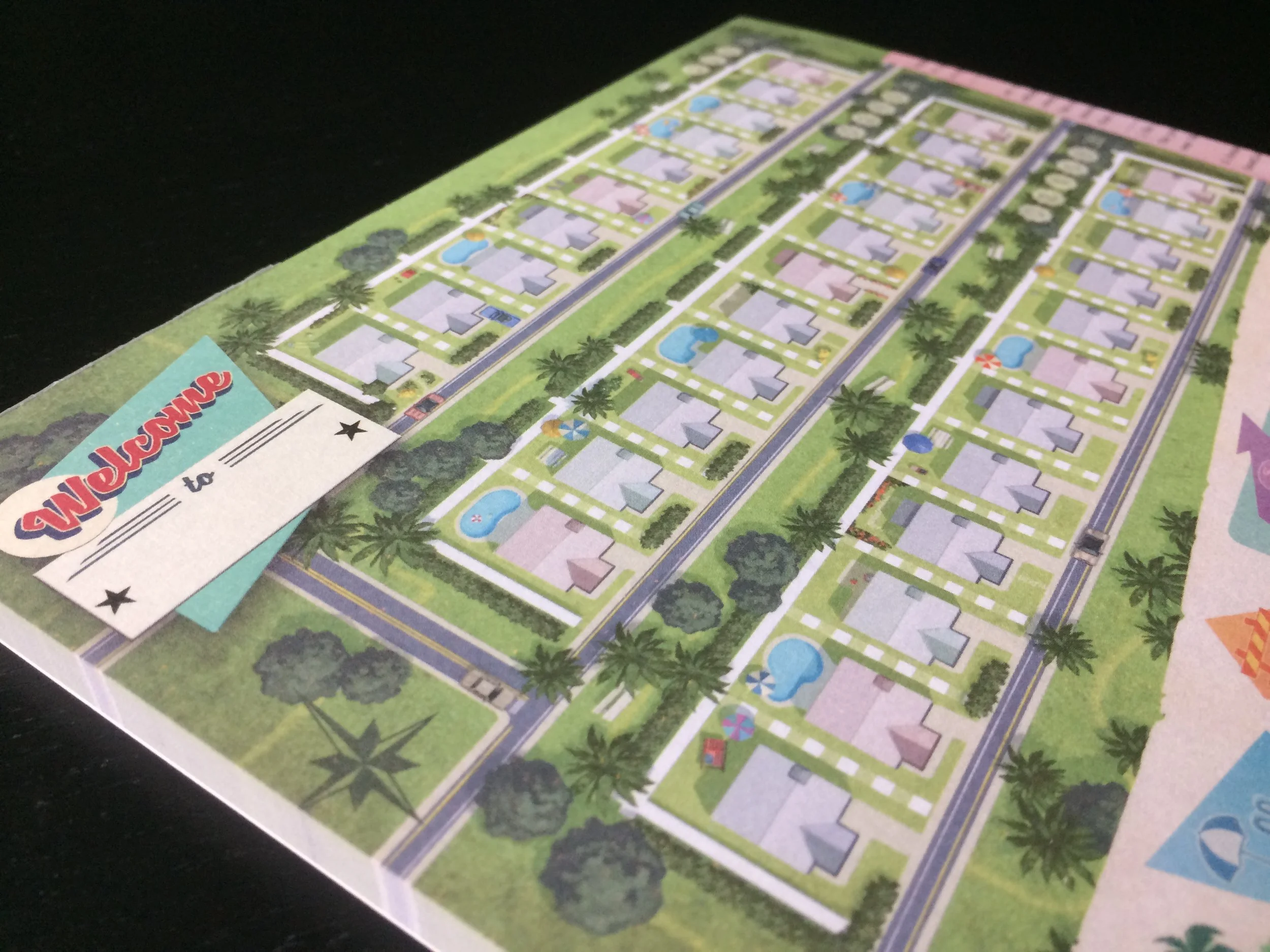

Meaningful Decisions: Benoit Turpin on Design Choices in Welcome To...

/In our Meaningful Decisions series, we ask designers about the design choices they made while creating their games, and what lessons other designers can take away from those decisions.

In this edition, we talk with Benoit Turpin, the designer of Welcome To…, about roll-and-write games, randomness and control, low-interaction designs, game rhythms, and more.

Welcome To... is often grouped together with roll-and-write games despite the fact that it doesn't have any dice. Instead, the game uses a deck of cards to control the random output from which players select their actions each round. Was this core system always the same, or did it change during development?

Actually, not at all. The core system was originally dice-based. You had three custom D8 dice with a color and a number on each side. You rolled the three dice and then combined them two-by-two, numerically and chromatically. For example, you would get a 2 blue and a 3 yellow, and that would make a 5 green. So you had, in the end, three combinations with numbers ranging 1 to 16 and six different colors corresponding to the six effects. That was the system I came up with, with the express desire to make a game system as pure and elegant as can be. Three dice and nothing more; but lots of possibilities. So at its core, Welcome to... is definitely a roll-and-write.

However, during the development phase, two things came up: One, the game length was too long. Around 40 to 45 minutes a game. And a good chunk of the game was dedicated to figuring out the three combinations each turn (six mathematical operations every time). And one of our playtesters (a local store owner) felt that the game was not a dice game in the sense that the player rolling the dice had no benefit compared to the other players. He was just “the Randomizer” (a cool title but still...).

So we went on looking for a better way to randomize the results (after a brief but painful phase where I had to say goodbye to the basic principle of my game--a necessary evil and a good lesson for a new game designer like me, but ouch...). The first goal was to replicate purely the dice roll without any dice. And we tried many things, from tokens pulled out of a bag, tokens dropped on a board, and many variations of card dealing. It was not easy to replicate the breadth of possible combinations without having an insane amount of components or a very clunky interface. But when we tried the card system present in the final game, we knew we had found the solution. Having the combination created by pairing the different sides of the cards allowed both the replication of the dice randomizer to a T, and got rid of the lengthy math phase. Suddenly, the game was 15-20 minutes shorter.

And from there, new options came: altering the gaussian bell curve to better fit the flow of the game; adding the effect on the top part of the number side to give player a bit more info to make their decision; and also, quite naturally, give the players a sense of control to the randomness. So, even though this “better control of the randomness” is often hailed by reviewers as a key part of the game system, it is just a byproduct of a completely different game design issue… And from my perspective, controlling randomness is important but not always a good thing...

Are there things that designers of roll-and-write games (or flip-and-fill games, as Welcome To… has been called) can or should do to mitigate randomness and give players more predictability or control?

In a roll-and-write, randomness is structurally a factor players have to take into account. Sure, there is a wide range of randomness from Yahtzee to La Granja: No Siesta, but if there is no randomness, then it is not a roll-and-write. It becomes a very different type of game, more akin to worker placement or action selection than R&W. So mitigating randomness should not be the ultimate goal when designing a R&W. For example, in Welcome To..., players can know the distribution of the cards, and can do a bit of card counting, but we limited this control by allowing at least one reshuffle of the deck during a game. Why? Because if players had access to complete information, then AP (analysis paralysis) could set in, and the game would just be a solvable, dry math problem. And that’s no fun… (at least for me).

So “things designers can or should do to mitigate randomness” are two very different questions...

Should they do it depends on the kind of experience they want to create. For example, Avenue has more randomness than Welcome To... and it gives a very different feeling: more highs and more lows because players are less in control, so they enjoy more having a break (feeling lucky is feeling good) and whine more (or is it just me?) when the fourth golden card comes too soon. And it is not a problem at all. It makes the game more accessible thanks to the lack of mitigating mechanics. It also can make games meaner, in Qwinto most notably. In Qwinto, the design is so sparse that there is very little luck-mitigating elements. And it can feel brutal sometimes. But this feeling is also explained by the type of randomness involved in these games.

Qwinto and Welcome To... share some similarities (most notably the three lines of ascending numbers) but the type of randomness in these games are very different. Qwinto has what is called output randomness: players make a decision (roll one, two or three dice) and then the die roll gives a random result and players have to deal with it. The designer mitigated the randomness using two tactics: First, by allowing the players to choose which die to roll, he gave the players control of the bet they were making. And then, the players can reroll if the result isn’t satisfying. But as you made your decision beforehand, the stakes are very high with each roll.

In Welcome To..., there is rather input randomness: players are randomly dealt three choices beforehand, and then they decide what to do with it. This type of randomness gives the player a bigger sense of control (it’s the same one you get in euro-style games; whereas output randomness is more akin to “ameritrash”). You pretty much always have the opportunity to adjust your strategy to the random result, and you get a feeling of “building something” more coherent. But at the same time, you won’t quite get the thrill of rolling the perfect number after sticking to your bet. You do get a bit of it, bingo-style, waiting for the 10-pool you so desperately need, but the stakes are lower.

So “should” is very much a design philosophy, and many great games went opposite routes on that.

As for “can,” designers have a very large panel of options. The most frequent design strategies are allowing the players to re-roll, allowing some players (usually the passive players in R&W) to refuse using the results; and giving several options to pick from the random result: In Ganz schön clever, for example, as the active player, you get to reroll and pick from several dice.

Designers can also use modifiers, powers that allow the player to manipulate the result of the die roll (+1 to a die, turning a die on its opposite side, etc.). For cards, Welcome To... uses a system where players know the effects of the next turn, but not the numbers, so that they can form a bet, akin to the dice selection in Qwinto. In Roll to the Top!, the designer used another system where players can adjust the random factor of the die by picking a different die, from a D4 to a D20, forcing the players to choose between safety and potential high rewards, which is pretty smart.

But personally, one of the best ways to mitigate the randomness is not by controlling the die roll or card flip, but rather by giving the players decisions to make after the random result. What I mean is that if the only thing to mitigate the luck you have is to act on the die roll, you will feel pretty helpless once you used all your tricks (rerolls, modifiers, etc.) if you have only one place to put your result in. Just imagine playing Qwixx by rolling one white die and one colored die (that you chose). You would feel very dependent to the randomness. As soon as you give players options on the result (which dice to use in Qwixx, which line to write your number in Qwinto, which route you connect in Avenue), then not only do you mitigate the luck, but you give the players a feeling of control over their game. And the best games are those where this decision is crucial because whatever you do, you always give something up in the process.

There are various ways to score points in Welcome To..., which allows players to pursue a variety of strategies. At the same time, each score track is capped at a certain number, which usually forces players to diversify at least somewhat. How did you settle on this approach?

Even though all score tracks are capped in Welcome To... the way they are capped is different. The goal of this is to give the game different rhythms. Parks have a very low cap, meaning you can get a feeling of achievement during the game, giving it a rhythm of small victories after another. Pools, on the other hand, have a very high cap: You aim for the target and fail most of the time, until that one epic moment when you finally get all the stars aligned and complete all the pools. It gives a different feeling for the player. Temp workers have a very high cap as well, so that you wouldn’t focus on it but rather on the race with the others. As for the real-estate agency, the rather low cap was made to avoid creating too big of a discrepancy between players not using the real estate and players using it. It was for balance purposes only. As for the Bis, I’ll get to it later on.

The way we settled on this approach was intense playtesting, trying all strategies to balance the game while aiming for different feelings corresponding to the different strategies. And the last phase of the development--with the graphic designer--helped us also define the structure of the score tracks. We needed something simple and common to all score tracks to make it easy for the players to follow their progress. The way Anne Heidsieck implemented that with the effect always being “crossing off the topmost available box” and the result always being “the topmost non-crossed box” was amazing but not compatible with other ways we explored without any cap. So it took the whole development for us to reach this final state.

How much leeway should designers give players for certain kinds of experiences? Are there times when giving players more or less freedom to pursue one strategy single-mindedly is appropriate?

All depends on the amount of leeway a designer wants to give the players… Giving a lot of freedom to players is a great but risky approach because if you remove any incentive to “play well,” you run the risk of having players playing very poorly and blaming the game for it, or feeling very bad.

For example, in Avenue, you are free to do pretty much what you want with each card. That can lead to very wide scoring differences (from -10 to 120 in the same game at my house) which can be frustrating but also exhilarating for players scoring very high, because they feel they earned it completely.

Usually, you need some kind of control over which strategy the players will use or you risk having a flaw in your game design.

For example, in Qwixx, you cannot end a line without having five numbers crossed previously, to avoid rushing. In Avenue, you have the “-5 if you don’t score more than the previous village.” In Twenty-One, you must cross off the numbers from the left to avoid players biding their time. In Ganz schön clever, the designer used different caps for the scoring tracks to give leeway to the players. They can play purple and orange as much as they want, while the others are more constrained. But he used the foxes to balance out that leeway (to paraphrase the rugby quote, “no fox, no win”).

I don’t pretend to know all the designers’ intent, but from an outside perspective, giving a sense of freedom to the players is probably better than giving them actual freedom (but don’t put that out of gaming context... it sounds awful).

The box for Welcome To... says 1 to 100 players can play at a time, but theoretically any number of players can play at once if they all have a play sheet. This makes the game a relatively low-interaction affair. Was this always your intention?

The very first iteration of Welcome To… was much more “take that-ish” than the final game, but this high interaction brought so many problems that it got cut off progressively during playtesting. At first, players could lock out other players from certain estates, or lower the value of their estates. But that created timing issues in a simultaneous game and could not be properly scaled for a large number of players. It was also some of the most hated parts of the prototypes during playtesting.

It is very difficult to have high interaction in a roll-and-write due to its indelible nature (at least until now) and its tendency toward simultaneous play. And we felt it was not a needed feature in the game.

Not all games need high interaction between players, and there are many advantages to low (but not altogether absent) interaction. As soon as we settled on this gameplay, we tried to remove any hurdle to higher numbers of players, especially around balancing issues. For example, we made the City Plans scalable to any count by allowing all other players to score the lower value of the card. Being first still mattered, but then everyone could still play.

What can designers of low-interaction games do to make their game accessible to a wider range of player counts?

Well, should they? Sure, it is always great to put on the box “1 to 100 players” as it is a good marketing tool, but using such a scale is very rare and probably not very interesting. And games such as Ganz schön clever did not need any of that to succeed: It doesn’t scale very well, especially at four players, but no one cares because it is such an amazing one- and two-player game. Players (and publishers) tend to want everything: a 1-100 player game with high interaction, fast-paced but strategic, deep but fun, thematic but thinky... But I believe a game should fit a specific niche rather than aim at the impossible and remove what makes it unique.

That said (sorry for the rant), if designers want to make games accessible to a wider range of player counts, there are a few things they can do. First, they have to look at it from a component perspective. To have a higher count, you need to take into account the need for each player to have all that they need. Roll-and-writes are structurally pretty good at this because you can put all a player needs on the sheet, without any need for multiple copies of tokens. Other designs need to find a way to minimize component gloat.

One way is to adapt your gameplay to fit that structure: You cannot have any mechanism that requires players to grab central tokens. You cannot have a “complete race,” with every position mattering. You cannot have limited action spots for a turn. Working on the sequel to Welcome To… with the express goal of making it also 1-100 players, I felt a bit limited in my scope of mechanics when I wanted to interject some interaction. I had to rely on a few that scaled well: majority, semi-racing (first gets better, rest gets a little).

You can also stick to “non-interacting mechanics,” with which you’ll have greater freedom. In games like Qwixx or Noch mal!, all passive players can pick from the “remains” of the active players. You can also have games where everyone use the same random result: Criss Cross, Knister or Avenue, for example; the variability coming from the individual positioning. From that initial stance, then designers can go to any mechanics that don’t affect other players (route building, hand management, etc.)

But at some point you must also consider simultaneous play (or semi-simultaneous with passive players still engaged on the active player’s turn). You probably will have to turn away from turn-based, drafting mechanics because variability in game length can be a dealbreaker if you want to increase player count.

The Bis action allows players to advance more quickly toward completion of a goal card, but at a penalty. How did this action come about?

It started as an action that let players write the card number next to a previously written identical number: You have a 7/Bis card and if there is a 7 somewhere, you can place another 7 next to it. It was meant as a tool for players to soften the harshness of the draw and erase some of their missteps. But it was very random depending on your game state and not that effective. Then we switched to “you place a 7 and then you can place another 7 next to it.” But it was clunky and also too luck-based. So we went to the actual Bis action: You can place a 7, and then anywhere on the board, you can write the same number next to a previously written number.

Bear in mind that it was developed before the City Plans/goal cards. So it was useful for players to get themselves out of a tight spot and finish a housing estate. It became much more powerful with the goal cards as it was also a way to race these. So we had to come up with a penalty. And there came into play psychological balance... We first gave a fixed penalty for each Bis. And it was statistically pretty balanced. But players refused to use the Bis action, seeing it as too costly (which it wasn’t). It was left unused, except by experienced playtesters who would crush the others by rushing Bis. By switching to a more progressive penalty, we almost completely erased that psychological barrier, and people started using it way more, even though it is statistically costlier today.

Are there things you learned from developing the Bis action that would help other designers who want to allow players to take risks in pursuit of a goal?

The most important thing is to make sure there is a real risk. If the action is just an alternate way of progressing through the game at a faster pace for a cost, there is a chance that some players will be able to math out the equation and find the exact amount of Bis that should be used. In Welcome To..., you are not guaranteed that your bet will pay off. If you fail to get goal cards or finish up housing estate even though you used Bis, because other players played differently, then it was not a worthy strategy. And that is important.

Another thing, as I mentioned before, is psychological balance. If your gain-to-risk ratio is perfect but players feel that it’s too good or too hard, then you have a design problem. And it happens in great games. And you can’t math-talk your way out of it. Players’ perception always wins, even when they’re wrong. And it is hard to make sure both mathematical balance and psychological balance are fine.

Finally, this action revealed an unexpected boon: It speeds up the game by cutting 2-3 turns. And in this day and age of impatient gamers, that is pretty interesting (and it led to a fun new action in the sequel). It turned out well for us, but I think it is important to look further than your expected target when introducing a new action like that because it can lead to unexpected results, both ways.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

ADVISERS: Rob Greanias, Peter C. Hayward, Aaron Vanderbeek

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole (Escape Velocity Games), John du Bois, Chris and Kathy Keane (The Drs. Keane), Joshua J. Mills, Marcel Perro, Behrooz Shahriari, Shoot Again Games

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Joshua Buergel, Luis Lara, Neil Roberts, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Dark Forest Project, Stephen B. Davies, Adrienne Ezell, Marcus Howell, Thiago Jabuonski, Doug Levandowski, Nathan Miller, Mike Sette, S GO Explore, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Cardboard Fortress Games, Kiva Fecteau, Guz Forster, Scott Gottreu, Aaron Lim, Scott Martel Jr., James Meyers, The Nerd Nighters, Matthew Nguyen, Marcus Ross, Rosco Schock, VickieGames, Lock Watson, White Wizard Games