Nikki Valens on infusing story into games, updating old editions of a game, and more (audio):

http://ninjavspirates.libsyn.com/who-what-why-s19e08-games-that-tell-stories-with-nikki-valens

Tips & Resources for Board Game Designers

Nikki Valens on infusing story into games, updating old editions of a game, and more (audio):

http://ninjavspirates.libsyn.com/who-what-why-s19e08-games-that-tell-stories-with-nikki-valens

Designing games for children and designing games for contests (audio):

The Game Crafter Legacy Challenge

Deadline: Feb. 4, 2019

Prizes: games, shop credit, and more

https://www.thegamecrafter.com/contests/sporktopia-legacy-challenge

How to work with an artist or graphic designer (video)

In our Meaningful Decisions series, we ask designers about the design choices they made while creating their games, and what lessons other designers can take away from those decisions.

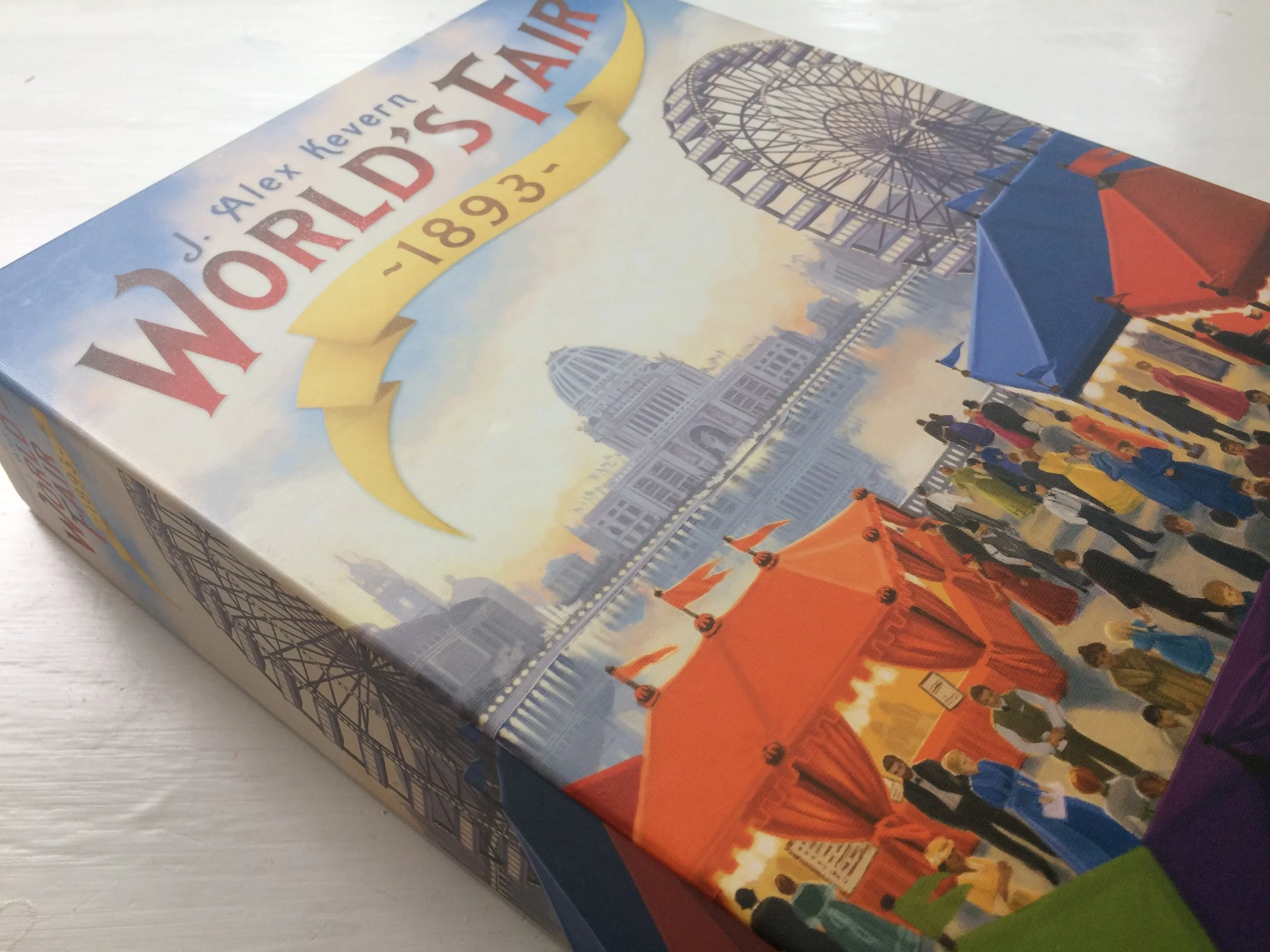

In this edition, we talk with J. Alex Kevern, the designer World’s Fair 1893, about guiding and incentivizing players, cohesion in a design, identifying your audience, the development process, and more.

Players start World’s Fair 1893 with a certain number of supporters already on the board. They also receive a bonus based on where they are in turn order. Was this always the case, and how did you settle on the specific setup rules to get players into the meat of the game from the first turn?

In the initial prototype, players chose their starting spots in reverse turn order. For more experienced players this was a good solution, but for players new to the game, they would either choose a spot randomly, or agonize too long over it.

We decided the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze, so we settled on assigning the starting placements based on turn order. Those later in turn order get more “sole” majorities to start, and more placements on locations with lower card limits where there will be less future competition. This provided the needed balancing, without bogging down the start of the game.

What determines how much early guidance players should receive, without being too heavy-handed or too lax?

As designer I think the best thing you can do is make the value of things explicit. If you can clearly articulate what is rewarded in the game, players know what they are shooting for and they can fill in the gaps of how to get there themselves.

In World’s Fair 1893, the primary ways you earn points are by a) having majorities, and b) matching your exhibit cards to where you have those majorities. Players can then fill in the gaps and quickly figure out that placing a supporter in an area that contains an exhibit card of the same type is a good decision, especially if it also gives you majority there. I’ve found players often grasp this even on the first turn of their first game.

Where you need to be a bit more heavy-handed, like pre-determining the starting placements, is where the value of things is more obscured. There is inherent value in having your starting supporters in the Fine Arts and Electricity areas, as each of those locations can only hold up to three cards (as opposed to four in the other locations), so there are typically fewer supporters placed there over the course of the game--meaning more value for each supporter placed there. Given that’s not something less experienced players would be considering, it made sense to be more prescriptive with something like starting position.

Every turn, three cards are added to the board, but each location can hold a maximum of three or four cards. Why implement a cap rather than allow cards to continue stacking up at a location until a player takes them?

We did do some early testing without a cap, but it often led to too few interesting locations to choose from each turn. Once a location reaches three or four cards, it will always be a viable option for players to consider, so there wasn’t a reason to continue incentivising that spot, as it would end up being chosen within the next few turns anyway. It made more sense to improve the other locations, increasing their viability, and creating more interesting options for players to choose from.

How can a designer know when it's better to add hard restrictions and when it's better to let incentives guide the player experience?

Typically I think hard restrictions--like strict hand limit--are only necessary when not having one would a) potentially break the game, by pulling too many cards out of the deck, for instance, or b) ruin the experience for the other players playing in the spirit of the game. Otherwise, if you want to keep buying Copper cards in Dominion, for example, that’s fine--there are plenty in the supply, and it’s not impacting the other player’s ability to pursue their legitimate strategy, so you can just enjoy your coppery deck until the game ends.

However, if you do find you need to impose something like a hand limit, sometimes it can be enforced through a game mechanism rather than a strict rule. For example, there’s no explicit hand limit in Catan, but anytime you have more than seven cards, you must discard half of them when a 7 is rolled. Other games allow players to take cards from the player who has the most. So there are other ways of enforcing various “soft” limits on things, rather than simply putting a hard cap on it.

World's Fair 1893 went through an extensive development process after it was signed with Foxtrot Games. What core ideas guided that process?

We knew we wanted to make a gateway-style game, with cohesive mechanics and interesting decisions. The idea of cohesion guided a lot of the development process--for example, originally the cards that moved the ferris wheel “game timer” forward were something separate from the Midway cards. There were only nine or 10 of these “timer” cards, and the round would trigger once four were taken, which made round length far too variable (presumably, all four could come out in two turns). After trying a few different things, we discovered the solution of making the Midway cards the game timer--there were a few dozen of them in the deck, which meant that the round could end after 12 or so were taken, leading to a much more predictable round length. It also removed a whole superfluous element from the game, and created something that was much more cohesive.

It could have gone a different direction, where instead we could have added cards or mechanisms to make it work properly. But, because of the style of game we wanted to make, we were focused on a development process centered boiling down rather than building up.

What should a designer keep in mind during the development process? How can they know what to try to hold on to and what to let go?

The most important thing is articulating what you want the game to be, its purpose, and who is the intended audience. Developing a game that you are intending to be played by experienced hobby gamers will be very different than developing a game you want to be in the conversation for the Spiel des Jahres. If you can articulate what type of experience you are trying to create, from there you really just have to “listen to the game.” It will tell you what it needs--more player control, more long-term strategy, less analysis paralysis--and it’s up to you as the designer to listen to those signals the game is telling you and figure out what adjustments to make. Playtesters can help you listen and help you hear new and different things, but in the end you have to trust your ears, and follow the sound.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

ADVISERS: Rob Greanias, Peter C. Hayward, Aaron Vanderbeek

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Chris and Kathy Keane (The Drs. Keane), Joshua J. Mills, Marcel Perro, Behrooz Shahriari, Shoot Again Games

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Joshua Buergel, Luis Lara, Neil Roberts, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Dark Forest Project, Stephen B Davies, Adrienne Ezell, Marcus Howell, Thiago Jabuonski, Samuel Lees, Doug Levandowski, Nathan Miller, Mike Sette, S GO Explore, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Cardboard Fortress Games, Kiva Fecteau, Guz Forster, Scott Gottreu, Aaron Lim, Scott Martel Jr., James Meyers, The Nerd Nighters, Matthew Nguyen, Marcus Ross, Rosco Schock, VickieGames, Lock Watson, White Wizard Games

“If you want to do something, it’s not important how you start. Just that you start. And then continue. And be willing to change and improve your project.”

Worker placement: how it works and how it came to be:

http://www.mechanics-and-meeples.com/2018/09/10/defining-worker-placement/

A checklist for the perfect Kickstarter launch day:

https://brandonthegamedev.com/how-to-have-the-perfect-kickstarter-launch-day/

Want to mitigate the effects of output randomness? Risk management could be the answer:

https://boardgamegeek.com/blogpost/80547/risk-management-home-much-maligned-output-randomne

“Friendly reminder to credit your playtesters in your rulebooks (within reason of course) or compensate them in some manner. No matter if their feedback is quality or changes your game, they spent their time playing your game and that’s worth something.”

Charlie Hoopes on the design process, finding a publisher, recovering from disappointment, replayability, playtesting early and often, and more:

https://goforthandgame.com/2018/09/06/a-conversation-with-charlie-hoopes/

Advice for running successful blind playtests (video)

How different designers approach their game's player count:

The requirement for the September 2018 24-hour contest is "bunny":

https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/2054080/24-hour-contest-september-2018

Different ways games can make use of cooperation vs. antagonism between players:

In this month's roundup of great board game design links, we have our own interview with a giant in the industry, tips for entering--and winning--design contests, advice from a newcomer who's been having a lot of success, and more.

featured:

contests:

rules:

licensing:

industry:

process:

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

ADVISERS: Rob Greanias, Peter C. Hayward, Aaron Vanderbeek

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Chris and Kathy Keane (The Drs. Keane), Joshua J. Mills, Marcel Perro, Behrooz Shahriari, Shoot Again Games

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Joshua Buergel, Luis Lara, Neil Roberts, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Stephen B Davies, Adrienne Ezell, Marcus Howell, Thiago Jabuonski, Samuel Lees, Doug Levandowski, Nathan Miller, Mike Sette, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Cardboard Fortress Games, Kiva Fecteau, Guz Forster, Scott Gottreu, Aaron Lim, Scott Martel Jr., James Meyers, The Nerd Nighters, Matthew Nguyen, Marcus Ross, Rosco Schock, VickieGames, Lock Watson, White Wizard Game

In our Meaningful Decisions series, we ask designers about the design choices they made while creating their games, and what lessons other designers can take away from those decisions.

In this edition, we talk with Bruno Cathala, the designer of the Spiel des Jahres winner Kingdomino, about putting restrictions on players, variable turn order, rule changes for different player counts, and more.

In Kingdomino, players select tiles using a drafting system that makes players weigh a tradeoff between getting a better tile now versus getting better drafting position next round. Where did this system come from? What other aspects of the design rely on it for the game to work as a whole?

This system is one example of what I call a “blessing in disguise.” In my games, very often, when I’m offering something very good to one player in the short term, he will pay a kind of counterpart. This is the case here: If you choose to draft the best domino, on the next turn, you will have no choice at all, just having to accept what other players don’t want. This kind of mechanism really helps to get a good balance.

One other aspect which is important in the game, is the distribution of different land categories. You have a lot of wheat fields and forests, but few crowns inside them. You have few gold mines or swamps, but many more crowns inside. And as far as points are, at the end, the result of multiplying the number of spaces by the number of crowns, you will be able to get a satisfying number of victory points, never mind the category of land you chose at the beginning.

Do games that allow players to vary turn order have any particular design considerations or pitfalls to avoid?

I like systems that break the basic “clockwise turn sequence” because it avoids having to always play after the same player. If the player is not very good, it gives you an advantage, and when it’s a very good player, you have a disadvantage. The counterpart can be increasing downtime, when you go first on one round, and last on the next one.

Players in Kingdomino must build their kingdom within a tight, five-by-five grid. This forces players to plan ahead or risk being unable to place a tile later on. Did the game always restrict players to that five-by-five grid, and what was it about that restriction that made you decide to use it?

In a game as simple as Kingdomino, tension comes from restrictions: If you were in a position to always place your tiles the way you want, you would lose some tension in the game. That’s the reason why I introduced two restrictions: You must be connected with your castle and/or to the same color, and you must stay in a 5x5 grid. Two simple restrictions which create a tension that increases throughout the game.

Also, it’s a way to introduce a little more interaction between the players. If I’m playing before you, I will make my choice analyzing what is good for me, and what could be absolutely bad for you. (Maybe I can force you to discard one tile because you have no solution.)

My first prototype, to validate the concept, was on a 4x4 grid, with eight dominoes per player. It was nice, but not long enough. So I increased it to 12 dominoes. At first, there was no castle, and players had to fulfill a 4x6 grid. But it was confusing for some of them. That’s the reason why Sébastien Pauchon (Jaipur), who is a friend and a talented game designer, suggested to me to add the castle tile, allowing players to play on a 5x5 grid.

How do you know if a particular restriction on players will be fun or just frustrating?

First of all, my personal theory is that frustration is the main mechanism which leads to games you want to play again and again. After your first game, if you have absolutely no frustration, you don’t want to play again. If frustration is too high, same: You don’t want to play again.

So I try to find a good level, which is not easy, because we all have our own frustration limits. For example, for some players, rolling a die and having no chance to change the result is too frustrating.

Then I have to say that I’m designing my games… for myself! I’m always working on the game I want to play. So the final balance for frustration is the one which is satisfying to me.

I consider a game designer to be someone who shows a path and then tries to convince people to follow him in that direction.

In the two-player version of Kingdomino, each player uses two pawns instead of one. This means players can and should plan further ahead each round. How did the rules for the two-player game come together?

This change to the rules was necessary to keep some tension during the choice of dominos with fewer players. Imagine that players have only one pawn. Selection would have been very automatic. No tension at all. So it would have been uninteresting.

As you know, I’m really a fan of two-player games. I myself play a lot at only two players. So I wanted the game to be interesting for two. I don’t like when it’s written “for 2 to X players” on the box, but with the game being very flat at two players.

So… It seemed to me that playing with two pawns could be a good solution. This was confirmed the first time I tried it.

And moreover, at two players, you can play on a 7x7 grid, using all the tiles, which is probably my favorite configuration.

When a game has to change some rules for certain player counts, how do you decide how different the game should be when it is played with that many players?

I don’t really care to have exactly the same game experience depending on the number of players. The thing which matters for me is to create the best game experience possible, never mind how many players you are. So, to keep that interesting game experience, I have no problem making the changes which seem necessary to me.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

ADVISERS: Rob Greanias, Peter C. Hayward, Aaron Vanderbeek

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Chris and Kathy Keane (The Drs. Keane), Joshua J. Mills, Marcel Perro, Behrooz Shahriari, Shoot Again Games

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Joshua Buergel, Luis Lara, Neil Roberts, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Stephen B Davies, Adrienne Ezell, Marcus Howell, Thiago Jabuonski, Samuel Lees, Doug Levandowski, Nathan Miller, Mike Sette, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Cardboard Fortress Games, Kiva Fecteau, Guz Forster, Scott Gottreu, Aaron Lim, Scott Martel Jr., James Meyers, Tony Miller, The Nerd Nighters, Matthew Nguyen, Marcus Ross, Rosco Schock, VickieGames, Lock Watson, White Wizard Games

Games about time travel: elements that have been implemented well and aspects that haven't been done yet:

How different designers find a theme that integrates well with their game's mechanics:

https://twitter.com/cardgamedesign1/status/1035345936187355136