Tips for making a sell sheet and getting in front of a publisher with it (audio):

http://thegamecrafter.libsyn.com/sell-sheets-with-the-game-crafter-episode138

Tips & Resources for Board Game Designers

Tips for making a sell sheet and getting in front of a publisher with it (audio):

http://thegamecrafter.libsyn.com/sell-sheets-with-the-game-crafter-episode138

“Playtest with a goal in mind – what about your game are you testing?”

In The Process, board game designers walk us through the process of creating their game from start to finish, and how following their path can help others along theirs.

In this installment, Geoff Engelstein describes how he created The Expanse Board Game, including working with licensed IP, creative constraints, keeping complexity in check, and more.

Process

Although I’ve designed many games prior to this one, this project had a number of “firsts” for me. It was my first game based on a licensed IP, it was my first design where I was specifically hired by a publisher to do a design, and it was my first with a deadline--and a short one at that, which would make it the quickest design I had ever done.

The timeframe was the biggest thing I was worried about when I took this on, but in the end it was a blessing. It forced me to focus, playtest earlier and harder than I usually do, and make tough choices. I have a tendency to “theory-design” in my head quite a bit before testing, to try to identify problems and strategies. It’s a bad habit. There’s really no substitute for testing a physical prototype.

For my day job I do engineering product development, and hitting milestones is a key part of being a professional, and not just a tinkerer. Having a deadline to complete a design really forced me to professionalize my process, set intermediate goals, and all the good things you should do on a project.

I’m a big believer in constraints aiding the creative process, and The Expanse reconfirmed my thoughts on that. I was given a specific set of criteria by WizKids: theme, component cost, complexity, play time, and when I needed to deliver. I’ve never designed like that before, except perhaps for Survive: Space Attack, but that was an extension of an existing game. My other original designs were all clean sheets of paper, and I could go in any direction I wanted, which makes it harder to settle on a final direction.

The Takeaway: Constraints, even if you’re just placing them on yourself, are important to keep you focused on what you’re trying to achieve.

Theory

I’m a big fan of The Expanse universe, and had a good idea of what I wanted to achieve. It’s very much about political maneuvering and posturing. While the threat of war is ever-present, war really doesn’t break out--at least not in the part of the series that was going to be covered by the game.

So, in spite of all the military deployments in the source material, a “dudes on a map” game like Kemet or Twilight Imperium really wasn’t going to work. It also wouldn’t fit the type of components WizKids wanted to use for this project. But the scope needed to be big, as the desire was for the players to represent the big factions in the game, not individual characters having adventures.

The key feeling I wanted to capture was one of spreading influence and pressure, which naturally translated into an area control game.

My main inspirations were the dual-use cards of Twilight Struggle and the COIN series, where other players might get to do actions based on cards played on your turn. As is my wont, I started too big, with too many options and mechanics. For example, originally every faction had different goals to win the game, there was an economic system, and there was a whole “tension” mechanic that governed what players were allowed to do.

These proved to push the game past the complexity we wanted for the target audience, and in any case didn’t really add that much interest. I ended up differentiating the factions by giving each a series of special abilities (called Techs) that are gradually introduced throughout the game. This controlled the complexity, by slowly introducing special abilities, but also recreated the tension mechanic by making it easier for players to attack each other as the game went on.

The biggest design challenge was making the Action/Event system work for multiple players. If the active player couldn’t or didn’t want to do the event on the card, who would get to do it? In the end, simplicity won out, with a basic priority system that added interesting choices, layered on top of a “card queue” system. The economic system got absorbed into the Victory Point system. Rather than adding a new resource into the game, players can spend VPs to do special things, and controlling bases that match the type of resource they need (like Food for the OPA), gives bonus VPs, which gives more spending flexibility.

The Takeaway: You can still be innovative while starting with something proven.

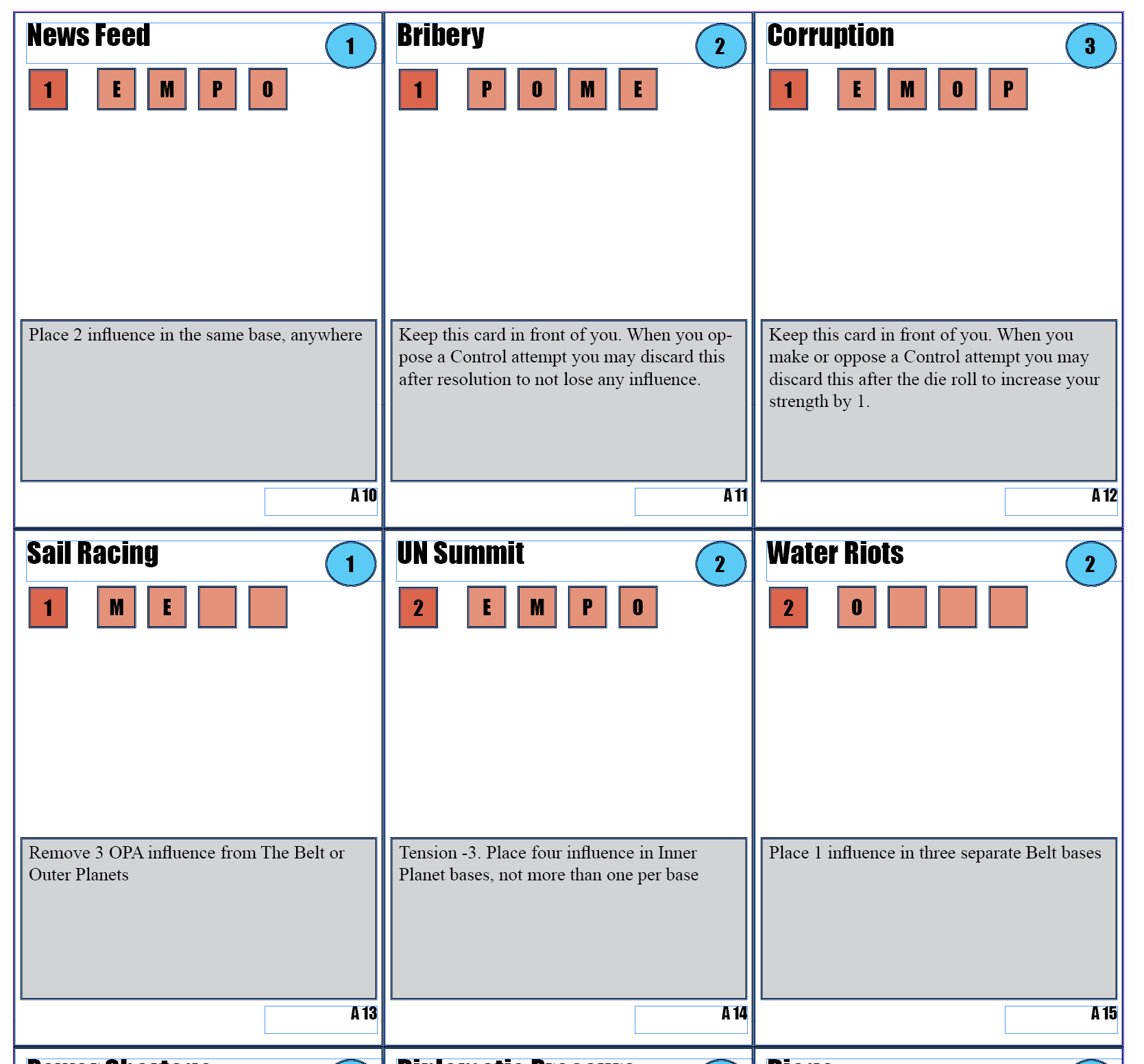

One of the earliest prototypes of The Expanse Board Game

Prototyping

Traditionally I design my cards with Adobe Illustrator. But I knew that I would have a lot of iterations of cards with a standard layout for The Expanse. So I decided to bite the bullet and learn how to combine Excel and InDesign to create merge cards.

It turned out to be not all that complex, and really saved me a tremendous amount of time iterating. It was easy to just change the Excel spreadsheet, and then the cards semi-automatically updated.

It also made it easier to supply the data to the publisher in a way that the graphic designer could use, and made it easier to check down the line.

For cards I also invested in a good paper trimmer. It was a little pricey, but the Carl 18” Heavy Duty Paper Trimmer was a lifesaver. I could cut out all the cards for the game in a matter of minutes. Being able to stack three or four sheets of cardstock and cut them quickly all at the same time made a huge difference. Recommended!

The Takeaway: Learn how to use all your tools--both software and physical.

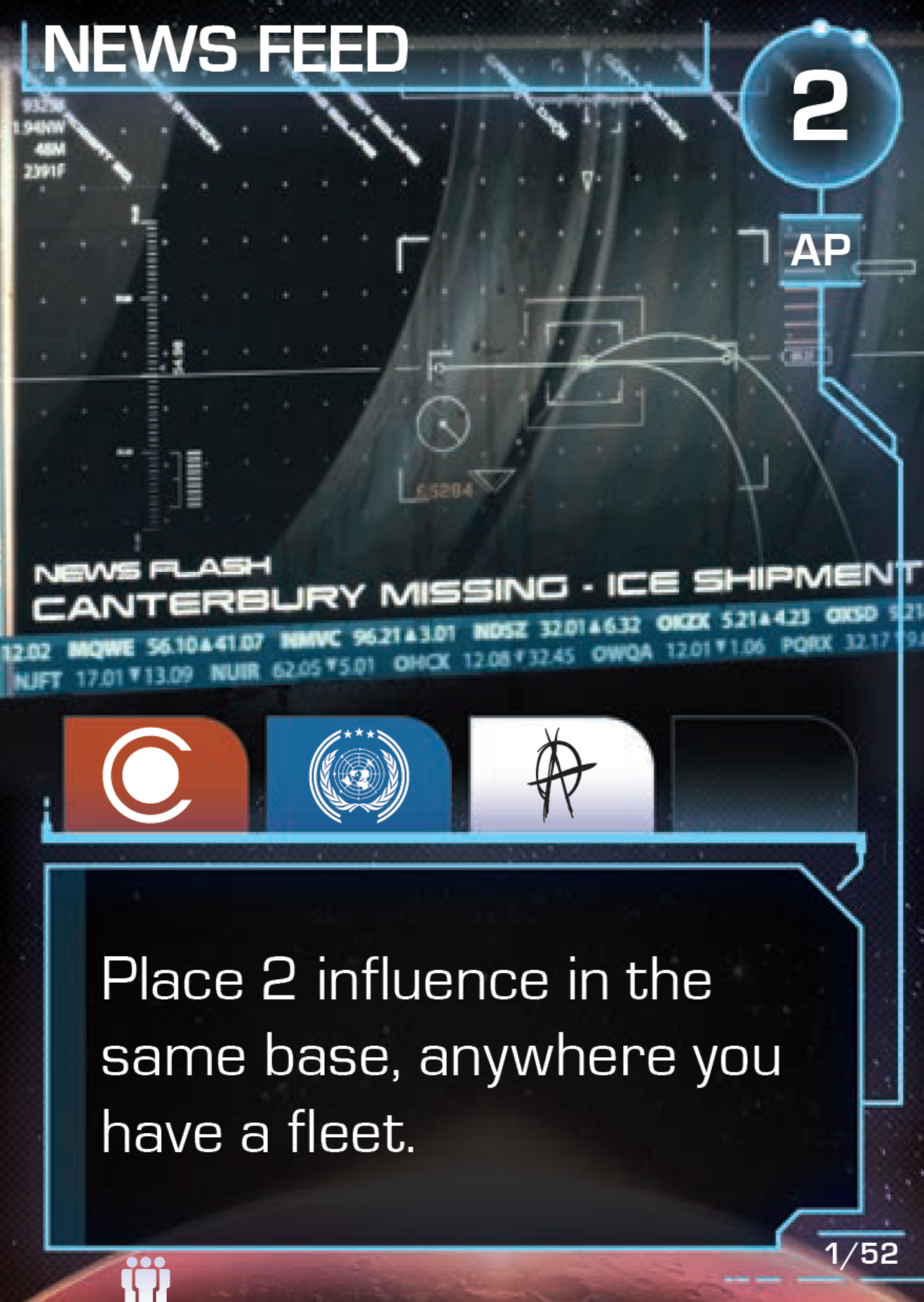

F inal artwork for the Newsfeed card

Playtesting

I was under a strict NDA about discussing the game, so I was limited in my circle of playtesters. I needed to get them cleared by the publisher, so I stuck to a local group of designers that worked with WizKids.

About halfway into the design I wanted to bring it to a local playtesting convention, Metatopia.The game had still not been announced, so we looked at a few options for having people there try it. Having players signed NDAs seemed challenging, and I didn’t want to worry about playtesters being spooked by that. In the end I ended up changing all the game elements--including card names, map locations and more--to remove all traces of the IP, and create a new backstory. It was a lot of extra work, but in the end it paid off and we got several great playtests in.

The Takeaway: Do what you need to do to get a wide variety of playtesters. It’s invaluable.

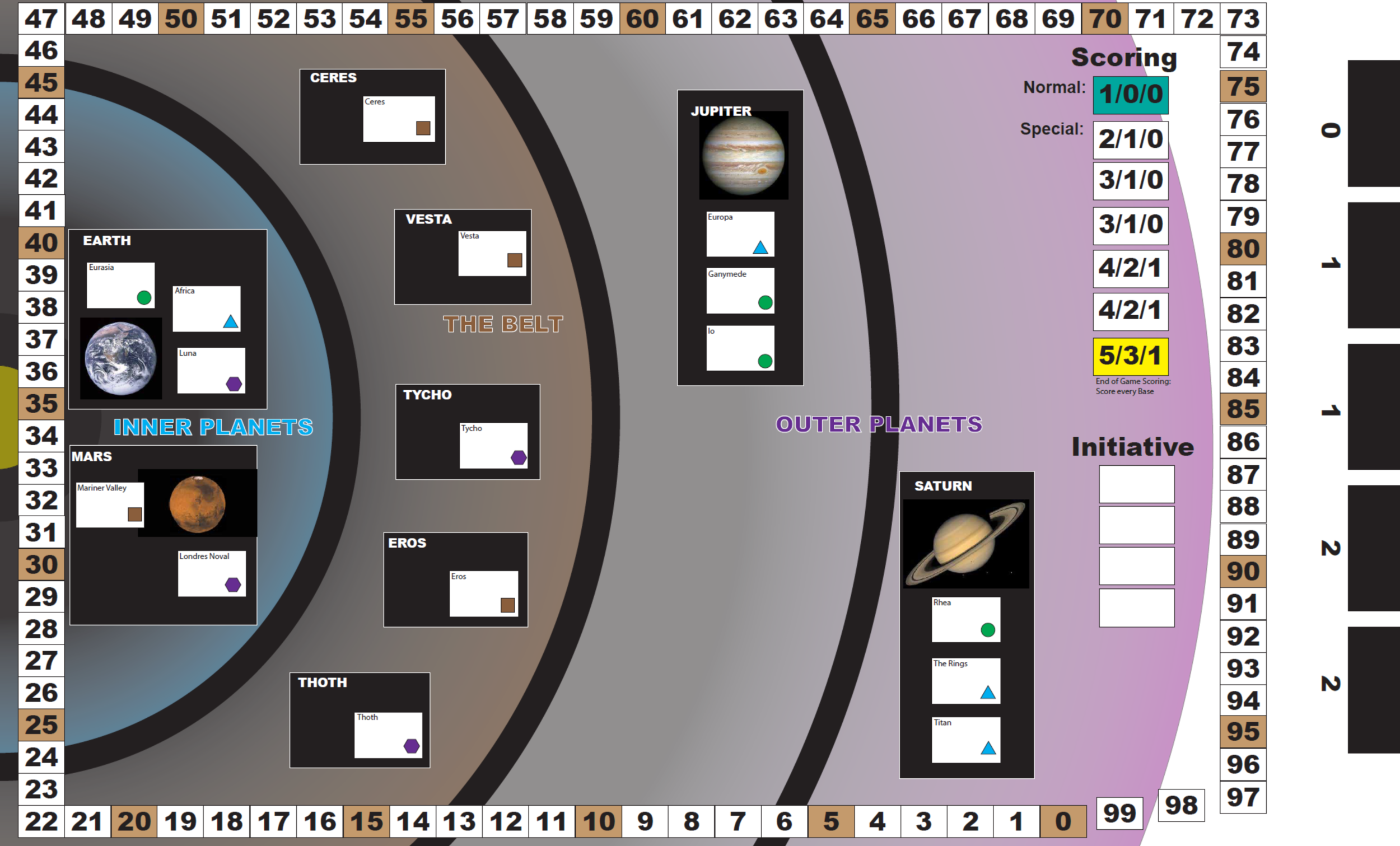

Map prototype that was submitted to WizKids

Conclusion

This was a different project for me, as it was a commission rather than me trying to pitch it to a publisher. However I did have to interface with the licensor for the IP, which was a new experience for me.

In spite of some horror stories I’ve heard about working on licensed products, I had a really good experience. The authors had good input, and patiently answered all my questions. We didn’t have big issues getting the artwork we wanted, and the graphic designer did a great job capturing the graphic look of the television series.

The Takeaway: Working on a licensed product provides strong constraints, which can be both good and bad. Designing under constraint can help to focus your efforts, but it may also limit creativity. You also have to consider the expectations that the fans are bringing to the table, as they expect the game to let them live within the world of the license, which creates a lot of pressure to deliver.

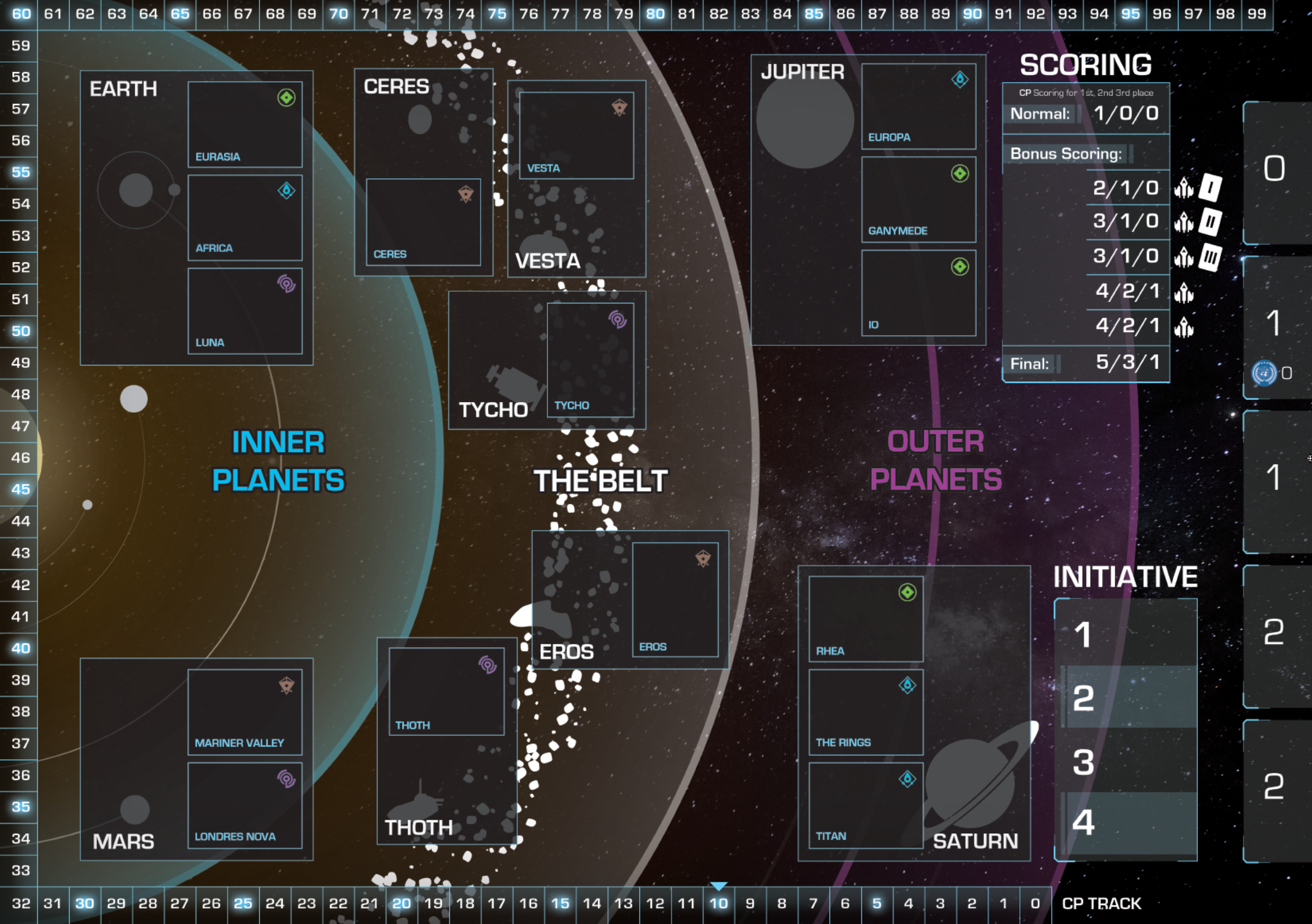

Final map for The Expanse Board Game

About

Geoff Engelstein is an award-winning tabletop game designer, whose titles include Space Cadets, The Fog of War, Pit Crew and The Expanse. He is also a noted podcaster. Since 2007 he has been a contributor to the Dice Tower, the leading tabletop game podcast, with a series on the math, science and psychology of games. He has also hosted Ludology, a weekly podcast on game design, since 2011, and recently published GameTek, a collection of essays on game design. Geoff teaches game design at the NYU Game Center, and has spoken at a variety of venues, including GDC, PAX, Gen Con, Rutgers and USC. He has degrees in Physics and Electrical Engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and is currently the president of Mars International, a design engineering firm.

Working with a distributor as a board game publisher (video)

Bankrolling a board game: adding up the expenses:

http://brandonthegamedev.com/bankrolling-your-board-games-development/

The different ways to make some money from a board game design (video)

A discussion about player experience, points, the design process, playtesting and more (audio):

http://cardboardarchitects.libsyn.com/designer-interview-tc-petty-iii-roundsomething

Mistakes to avoid as a small publisher (audio):

http://www.boardgamedesignlab.com/lessons-learned-as-a-small-publisher-with-marshall-britt/

“When a tester makes a suggestion that is ridiculous, don’t explain why it wouldn’t work. Write it down and move on.”

Results from a survey about what people like and dislike in games:

Tips for using BoardGameGeek during a crowdfunding campaign:

http://www.theindiegamereport.com/lesson-21-boardgamegeek-tips-and-tricks-for-kickstarter-creators/

The right ways to steal ideas:

http://itbboardgames.com/2017/08/17/how-to-steal-like-a-game-designer/

2017 Mint Tin Design Contest

Deadline: Nov. 21, 2017

Prizes: GeekGold

https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/1834478/2017-mint-tin-design-contest

Fastaval's Otto Award for Best Boardgame

Deadline: Sept. 1, 2017

https://www.fastaval.dk/call-for-synopsis/boardgames-2018/?lang=en

How to implement an "epic event" in a game:

https://davidmullich.com/2017/08/14/representing-epic-events-in-games/

How to network in the board game industry:

http://brandonthegamedev.com/5-easy-ways-network-board-game-industry-without-being-weirdo/

Get to know the groups of people that form the board game industry:

http://brandonthegamedev.com/the-board-game-industry-powers-that-be-the-hype-machine/

Ways to make a game shorter:

Things to remember before making board games a full-time job:

“Every game sucks at some point. If you don’t feel like your game sucks, you are not being honest with yourself.”