The Process: Cutthroat Caverns by Curt Covert

/In The Process, board game designers walk us through the process of creating their game from start to finish, and how following their path can help others along theirs.

In this installment, Curt Covert describes how he created Cutthroat Caverns, including how a new gaming group inspired the game, designing with your own sensibility, engaging players’ emotions, finding art on a budget pre-Kickstarter, marketing by word of mouth, the importance of customer service and more.

Theory

My company, Smirk & Dagger Games, is well-known for its design aesthetic, in that we specialize in “stab your buddy” games. I just think they are more fun--highly emotional, laugh-filled, curse-filled, fun.

Every aspect of Cutthroat Caverns was carefully designed to live up to that and was inspired by my early years of playing Dungeons & Dragons. You see, my high school D&D group was very Tolkien-esque. We were all pretty Lawful Good, “all for one, one for all” brothers in arms. (Actually, my 1980’s player group was entirely women, other than me, but that’s beside the point.) If you found a magical item, you gave it to the person who could best wield it. We were all true heroes.

Well, when I got to college and played the first time with a whole new group, it was quite different. Chaotic Evil alignments, selfish unscrupulous folk, assassins, true mercenary brutes, all of them. I shall never forget the horrifying moment that I suddenly realized that the other players in my party were far more dangerous than any creature the DM could summon. That feeling of shock and horror was the exactly what I wanted to recreate and perpetuate throughout Cutthroat Caverns.

So I started with the premise. You’re a group of adventurers who had vowed, by all you hold sacred, that each day the first pick of treasure would go to the person with the most prestigious kills--except today, you found “the one ring / the holy grail / the most glorious treasure imaginable” and now you will do anything to make sure that person is you. But this is a vicious dungeon, filled with creatures that will overwhelm and destroy you, and you must escape before you can claim your prize. As the box says, “Without Teamwork you’ll never survive. Without Betrayal, you’ll never win.” It is a game about “kill stealing” and gaining more prestige by landing more killing blows on the toughest creatures--before the other party members can. It was a simple enough construct--but lead to a pretty unique style of game play. Too diabolical to be called a semi co-op, I coined the term “cooperative backstabbing.”

The monsters in the game had to be deadly and the illustrations and mood of the game had to put players on the defensive. Each time an Encounter is revealed, there has to be a gasp around the table--an ‘oh, crap!’ moment, in which they fear for their lives. That perpetual feeling becomes the driving force to work together. Then, balanced in equal measure, each creature also provides a reward for your sudden and inevitable betrayal.

It was clear that the creature stats would need to increase with the number of players at the table, in order to keep the threat level appropriate. But I took this opportunity to assure that the player elimination aspect of the game, which can be polarizing for players, didn’t lead to anyone being pushed out too soon. I simply ruled that, should players die early on, the creatures you’ve yet to face would not get weaker. The creature stats remain set to the number of people who started the game and the remaining players may no longer have enough firepower to win. This encourages keeping your opponents alive in the first three quarters of the game, yet allows for player elimination in the end game, especially of the prestige leaders, to remain an important avenue for players to win.

I then turned my focus to the players and the core mechanics of the game. For thematic reasons, I didn’t want any straight-up, player-versus-player combat. After all, we are a team--right, Boromir? Instead, player conflict would be more passive aggressive, as you attempt to get other players hit more often by the monsters. I also decided, at the outset, that there would be no dice rolling in the game, especially in regards to combat. Those games already existed and I was hunting for a different experience. But more important, I wanted players to have a high degree of control over how hard or soft they would strike. I wanted an intricate dance as they jockeyed for position to land the killing blow. Borrowing initiative order from my days of D&D, players would know and could plan their strategy in secret based on turn order, but would have to “set” their selected attack without knowing how hard others would swing.

I was delighted to discover that cards doing little or no damage could be just as valuable as those doing a lot of damage. If you can’t kill the creature yourself this turn, your best play is to sandbag, hoping the creature survives long enough for you to kill it next round. Most players assume low cards are worthless and watching their faces light up as they discover their value is almost as sweet as watching the faces of those who feel robbed of a kill, because they had planned on you doing more damage. I love to see people discard low cards, knowing they still have much to learn about the game.

Of course, there needed to be “take that” cards capable of increasing or decreasing your attack strength, changing initiative, spoiling your attack completely, stealing items or reassigning damage as well as limited-use items to fight over, which never get shuffled back into the deck, to keep their intrinsic value high.

There were two design decisions that were long debated, Bonus Prestige and Character Abilities. One concern, early in design, was the emergence of a “runaway leader.” At some point, it could be mathematically impossible to catch up with the leader, and this drains the fun out of the endgame. One solution is for players to eliminate the leader or several of them at the end of the game, but this is not always possible. So I devised a somewhat controversial fix, Bonus Prestige. In Rounds 7 and 8, as the exit draws closer and the tension rises, creatures deliver 3 additional bonus prestige. In rounds 9+, five bonus prestige are added. This provides those trailing in prestige a means to catch up in the critical last rounds. It is an effective solution, but has been criticized by some who felt the first encounters mean almost nothing, so long as you score the final kill. In truth, it isn’t quite so, but it most certainly can make all the difference. But I could find no better solution at the time. Since then, additional prestige resources (Relics, for example) have mitigated this.

The second debated design consideration, perhaps the most hotly fought in development, was whether or not we should have asymmetrical characters in the game, granting players unique abilities. With the creatures changing the play environment every round, with different rules and exceptions, I felt strongly that player abilities would only further complicate the game. Worse, I was afraid that players would argue about the balance of the character abilities. I never wanted to hear, “If I’m not the Dwarf, I’m not playing. That’s the only way to win.” Instead, I wanted the sole focus of the game to be about the players themselves and what they were willing to do to each other to win. That was far more interesting and engaging game play, a social experiment almost. But my partner argued that when you play a fantasy adventure game, players want and expect that their characters will be unique. We were both 100% correct. I made the final call to go without. It was more important to deliver a game unique unto itself.

But fans echoed my partner’s position. In the first expansion, I tried a limited one-use ability to try and meet their demands, but I was never happy with it. Years later, with the concept of drafting more popular, I finally found a great solution. I allowed players to draft ability cards and then choose abilities they wanted before the game began. But for each they took, their maximum Life Totals would be decreased. The fact that they could construct their own characters removed the possibility of arguments over balance. In addition, we created 12 pre-set characters, should players want to play them, which were created from the ability cards used in the draft, theming the official characters of the game. I’ve been very pleased with how it came out.

In truth, the “tool kit” of mechanics and variables in Cutthroat Caverns are fairly limited and straightforward. And it is therefore shocking how much variety we have been able to deliver, in terms of unique encounters (of which there are now 140 or so), items and events. Each encounter drips with theme and plays very differently from one another. This variety, and the emotional impact the game delivers, is what brings people back, time and time again. I think it remains my best design.

The Takeaway: Create a glossary for your game at the outset, and live by it religiously. I’ve had a very rough learning curve on this with Cutthroat. Synonyms, alternate phrasings, inconsistent descriptions can all lead gamers to infer unique rules loopholes, where you intended none, or else lead to needless confusion. I’m sad to say, the game still suffers a bit from my sins of the past in this regard, but I’ve learned a valuable lesson for the future.

Without engaging the emotions during the game, there is no story to tell after the game. Epic betrayals, clutch plays, triumphant comes-from-behind--this is the stuff of legends. Playing your game should lead to great tales.

I love the delicate balance of cooperation and betrayal needed to win. There is such an amazing dynamic here and one I would love to see explored more in the industry.

The best designs allow your fans to contribute to the game. After our first expansion, I wanted to deepen the relationship with fans and their involvement in the game--just as I had done so many years ago building expanded content for games I loved. In Deeper & Darker, I included a surrogate encounter card that would be a placeholder in the deck for your own creature designs. A year later, I ran a contest to create a new encounter for the game. The winner would have their encounter considered for inclusion in our next expansion and they’d win a bunch of games from our catalog. Well, I was bowled over by the response. I thought I might get a few very rough ideas. What I got was almost a hundred well-considered encounters, which pushed the game into lots of new and innovative directions. Sure, we had plenty of work to do to balance and refine them, but it inspired and created game content for our next two expansions, including the Event deck of Relics & Ruin, and a slew of brilliant creatures like fan faves, WereBoar, Gluttony, Greed and Emperor Lich.

I learned the power of creating a “funnel” in the game. Since I wanted a specific emotional reaction consistently throughout the game, I had to define it and then find almost endless ways to elicit it with a handful of game tools--imminent death versus a host of possible rewards for risking the death of yourself and everyone else. Anything that helped funnel people towards making this critical decision was exploited and added to the game. Anything that did not was cast aside.

First rough concept for the Cutthroat Caverns box. Courtesy of Smirk & Dagger Games.

Process

The heart of game I set about designing myself, but I have always relied on my partner in crime, Justin Brunetto, to kick the tires and suggest areas to improve. And I try to learn something from every playtest. The design evolved over the course of a year where we debated wordings, how deadly to make the dungeon, bonus prestige and the final Encounters paired down to the best assortment.

My first step is always to mock up materials as rough as possible, for myself, where I play mock hands alone. This lets me see the game flow for the first time, identify very coarse issues, and make any adjustments before subjecting others to an overly flawed design. In Cutthroat, this initial runthrough allowed me to see the benefits of a damage stack of cards and verified the viability of printing adjusted damage along all four edges of the card, so they could be rotated to one side to show ‘half damage’ and the like.

I might ask family and friends to do one session with me, just to gauge the human element, but I never expect a great deal of reliable feedback here, as friends and family can be guarded on criticism. The real work happens with players who don’t know you. That is where all the learning is done, with all sorts of player styles.

I do not rush the process and a game is only done when it is ready. Often times, as primarily a one-man shop, I am weaving development time in after work at local game stores, on the weekends and comping and editing rules where I can find time. You can sense you are close when major rules questions begin disappearing. But for me, I know a design is done and worthy of printing when a playtest ends in a couple of the players excitedly asking me when the game will be available. If I have to ask if they like it, it probably isn’t ready yet.

The Takeaway: The design process for Cutthroat was fairly seamless. The final game was very close to the initial design, and my assumptions regarding how players would react given the situations I purposefully placed them in were dead on. Making sure the creature Encounters were balanced yet emotionally engaging was the fun part and then took some tweaking here and there.

Everyone approaches the design process differently. Some designers are more mathy, some are looking for intricate decision trees, while I stress a gut feel of gameplay delivering on the emotional impact of play. I want to see highs and lows, gritting of teeth and laughter. But no matter what your style, build and develop with your own sensibility at the heart of the matter. Build your game, no one else’s.

But be fluid, not every design is the same. Let the game itself guide you. Let playtests challenge your assumptions.

Prototyping

I come from a graphic art background, so prototyping was always second nature. I have a few tools that may not be as easy to come by for others, but there are easy replacements to be had.

First rule: First prototypes should not be pretty. You are testing core concepts, so keep it rough. You can even handwrite the cards if you want or just have black type on featureless cards. Make sure the core mechanics work before trying to make it look good.

Second rule: Editable prototypes are better than fixed, beautiful prototypes. Don’t run to The Game Crafter with your first prototype. You will be changing a lot in the process. My favorite thing for cards is to print out roughs on regular copier paper and drop them into card sleeves with a playing card backer (for stiffness). Anytime you have a rule change, swap the paper and you are good to go. Card sleeves of different colors can help separate different card decks.

Once I have a design that I’m fairly happy with, I will add a little art and design that help people imagine the theme of the game. That can impact how people perceive the game, helping put them in the world you imagine. I have often used clip art or other things “for position only” (it is good to mark it as such) before actually working with an illustrator to develop art. I would only do so once I had a very final design in place.

For chipboard tokens, game boards, etc., I tend to lay those out on tabloid (11x17) sheets on a computer. Illustrator, Photoshop and InDesign are industry standards. But you can hand draw them as well if you need to. But I typically run color lasers and then apply adhesive to the back with a Xyron machine. They can be bought at Staples and other such office stores. It is essentially a roller system that applies a uniform gummy coating to the back of your printouts, so you can then carefully adhere them to some nice art board, chip board or even heavy duty card stock. Without a Xyron, use 3M Spray Mount (light tack). Spray a very light, even coat (you don’t need much) and do so outside on a surface you don’t mind getting tacky.

Once I’ve got a solid design and developed/semi-developed artwork, I do a final comp that I can showcase with gamers, retailers and distributors. At this point, if you want to go to Game Crafter for a more professional level of finish, go for it. I don’t, but I do upgrade to clear sleeves and comp the back of the cards as well.

The Takeaway: A beautiful prototype can definitely help draw people in and get them involved in the game’s theme--but do so later in the process to save yourself some time and money.

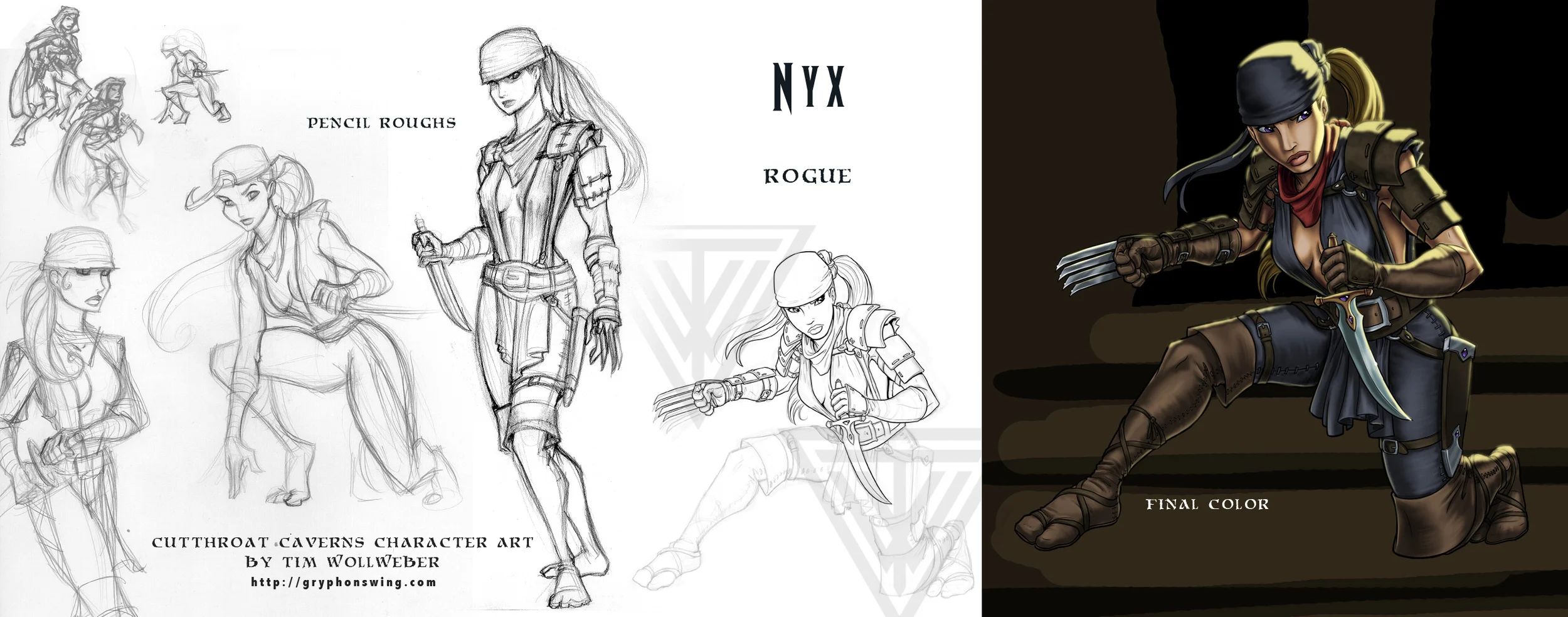

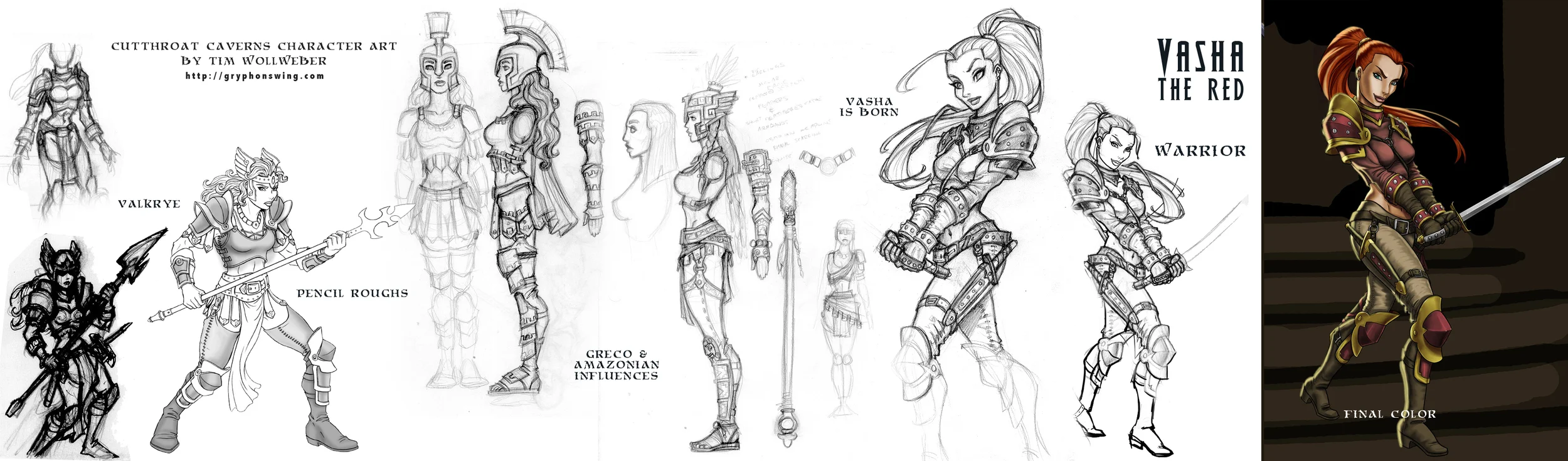

Cutthroat Caverns character design. Courtesy of Smirk & Dagger Games.

Playtesting

Until you playtest, you don’t really have a game; you have an idea for a game. It is in playtesting the game that you find all the ugly bits, prove out your concept and perfect it.

I’m big on playing with people I don’t know and often travel to board game meetup groups, game nights at retail stores and conventions to find gamers who are not friends and family. Some people go through the rigor of having playtesters write down their thoughts and ask specific questions, but I have often found that a quick conversation can be more meaningful. Let your players know that part of the test is chatting about it afterwards. If you have things you are specifically trying to get input on, by all means mention it. But a conversation will allow you to follow up with clarifications or even pull additional input from them. Try to avoid making comments or reactions that cause them to shut down. You can filter for what is useful later, but accept what you are given with open ears and an open mind. Evaluate later.

Don’t try to accommodate all the input you receive. Some will be smart, insightful and right for your game. Some you will discard as a direction you do not wish to move in. All input is important; not all is actionable.

On Cutthroat, our playtesting did indeed prove that players were interested in unique characters and asked why we didn’t have them. Most were satisfied with my answer about wanting to instead focus on the lengths players would go to achieve their selfish needs, but it didn’t stop them from requesting. In the end, I had to decide what game I wanted and why--and stuck to my guns. We reduced much of the grey areas in describing the unique rules pertaining to each creature.

Publishing

Cutthroat was the fourth title Smirk & Dagger produced. My previous games had generated just enough income to reinvest in the printing, but little else. Mind you, this was well before Kickstarter. My first games required me taking on a second mortgage to fund the printing, which took a long time to pay off, but this game scraped by on money I’d generated from the first three games. That said, I had very little available for art--and huge art demands.

The art was critical for the theme. I needed somewhat whimsical player character art to show that the game itself was light-hearted--and really awesome, nasty creature art that made you think these creatures would tear you all apart. It was the first time I had to go outside for illustrations, having used my own cartooning skills and graphic art ability on previous games.

It was important for the characters to be consistent in style, from a single artist. I found a great artist who had been working on his own comic book, with a style somewhere between Marvel and Disney art. His previous works were unpublished (officially) so I was able to work with him on a budget that worked great for both of us. We worked through pencil sketches right into final color art. I had him illustrate the characters as full body, standalone poses and planned to combine them into a composition for the cover art, to avoid having to create separate cover art.

Much as I wanted unique art for each Attack, Action and Item card, it was simply not possible, so I created graphic treatments for each, which were clean and functional. This left the creature art. I needed 25 illustrations and had largely run out of resources, certainly not enough to commission new works of art from scratch. So I decided to contact a handful of illustrators whose previously created works had caught my eye, with existing creature art that would suit the cards. All were personal projects they had done, in some cases years before. I worked out arrangements with each to feature their works as part of a very eclectic gallery of encounters. It was a unique solve and the diversity of styles became a strength for the game.

Marketing was very word-of-mouth, mostly convention appearances and reviewers whom I sent review copies to. I also submitted to the Origins awards and other award panels. Happily, the game itself did much of the work for us. It was innovative and despite a few rough spots in the rules (we’ve been through a number of improved versions) it garnered a lot of attention, earning a number of nominations for game of the year.

The art of the demo was critical in the success of the game. It takes 90 minutes to play and that is way too long for a convention booth demo. It took a while for us to figure out how to best show it. First, I created a “teaching board” with pictures of all the key cards neatly arranged. Instead of fishing out cards every time I taught the rules, I could just point to the right spot on the board. It cut teaching the game in half. Then we decided we could showcase everything about the game in just three or four encounters. We chose an example of a few very different encounters to highlight different mechanics in the game and dropped everyone’s life total in half to keep the danger level appropriate. It delivered the full experience in just 15 to 20 minutes. Still a long demo, but one that felt robust and full, and led very reliably to sales.

The Takeaway: For every game you design/publish, craft the shortest, best experience to showcase your game. Stack the deck, streamline setup, remove cards that lead to confusion, etc. The demo should be pretty consistent and show off the best aspects of the game. Above all, create an experience they will remember. I’ve always said that I never have to “sell” a game. I just have to show people what excites me about it.

Do not be stingy with handing out copies to podcasts and reviewers. Consider it part of your marketing budget, because it is--and the least expensive marketing you will ever do. Demos are the number-one best way to market your game, reviews are number two.

Customer service is critical. Professionalism is critical. Don’t be a dick. Ever. To anyone. Fans, artists, printers, reviewers and people in general. Show them your passion, treat everyone with the respect they are due, expect nothing and appreciate everything. This will always open a door--or at the very least, won’t close them.

Cutthroat Caverns character design. Courtesy of Smirk & Dagger Games.

About Curt Covert

Curt Covert is the owner of Smirk & Dagger Games and the designer of Hex Hex, Run for your Life Candyman, Cutthroat Caverns, Sutakku, Nevermore and a number of other titles that prove games are more fun when you can stab a friend in the back. He still has a full-time job as a creative director for a major marketing company and a very patient and understanding family. Smirk & Dagger will have an unprecedented number of new games in 2016, including Dead Last, our social collusion game of shifting alliances and betrayals, J’Accuse!, a game of accusations, denials and murder, and Specters of Nevermore, an expansion to our card drafting game featuring 12 unique characters based on Edgar Allen Poe’s literary characters.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Richard Durham, Peter C. Hayward, Matthew O’Malley, Isaias Vallejo

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Luis Lara, Behrooz Shahriari, Aidan Short, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Robert Booth, Doug Levandowski, Aaron Lim, Nathan Miller, Marcel Perro, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Kevin Brusky, Kiva Fecteau, Scott Gottreu, Michael Gray, JR Honeycutt, Scott Martel Jr., Mike Mullins, Marcus Ross, Sean Rumble, Diane Sauer