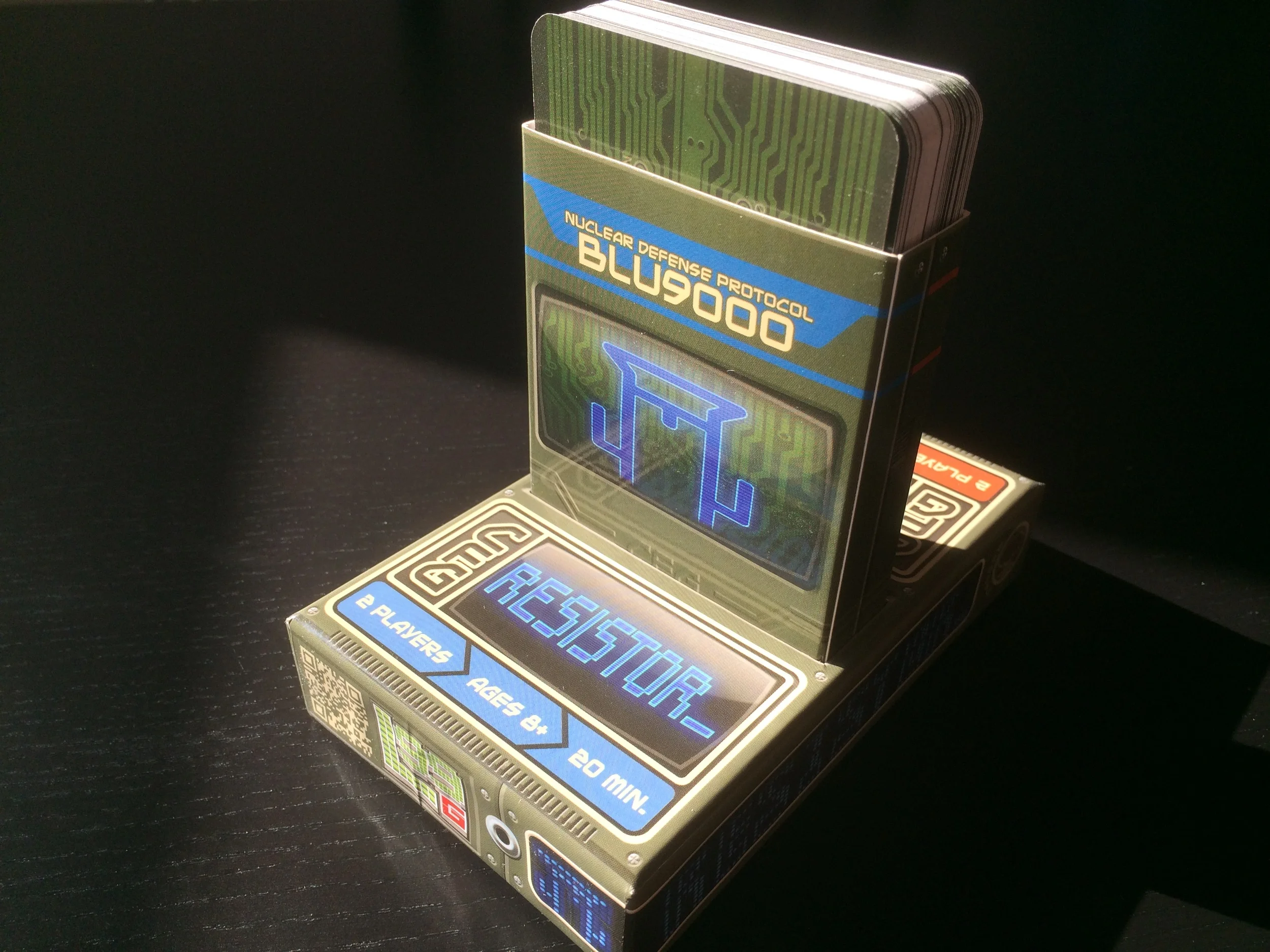

Meaningful Decisions: Anthony Amato & Nicole Kline on Design Choices in RESISTOR_

/In our Meaningful Decisions series, we ask designers about the design choices they made while creating their games, and what lessons other designers can take away from those decisions.

In this edition, we talk with Anthony Amato and Nicole Kline, the designers of RESISTOR_, about private and public information, shifting game states, two-player games and more.

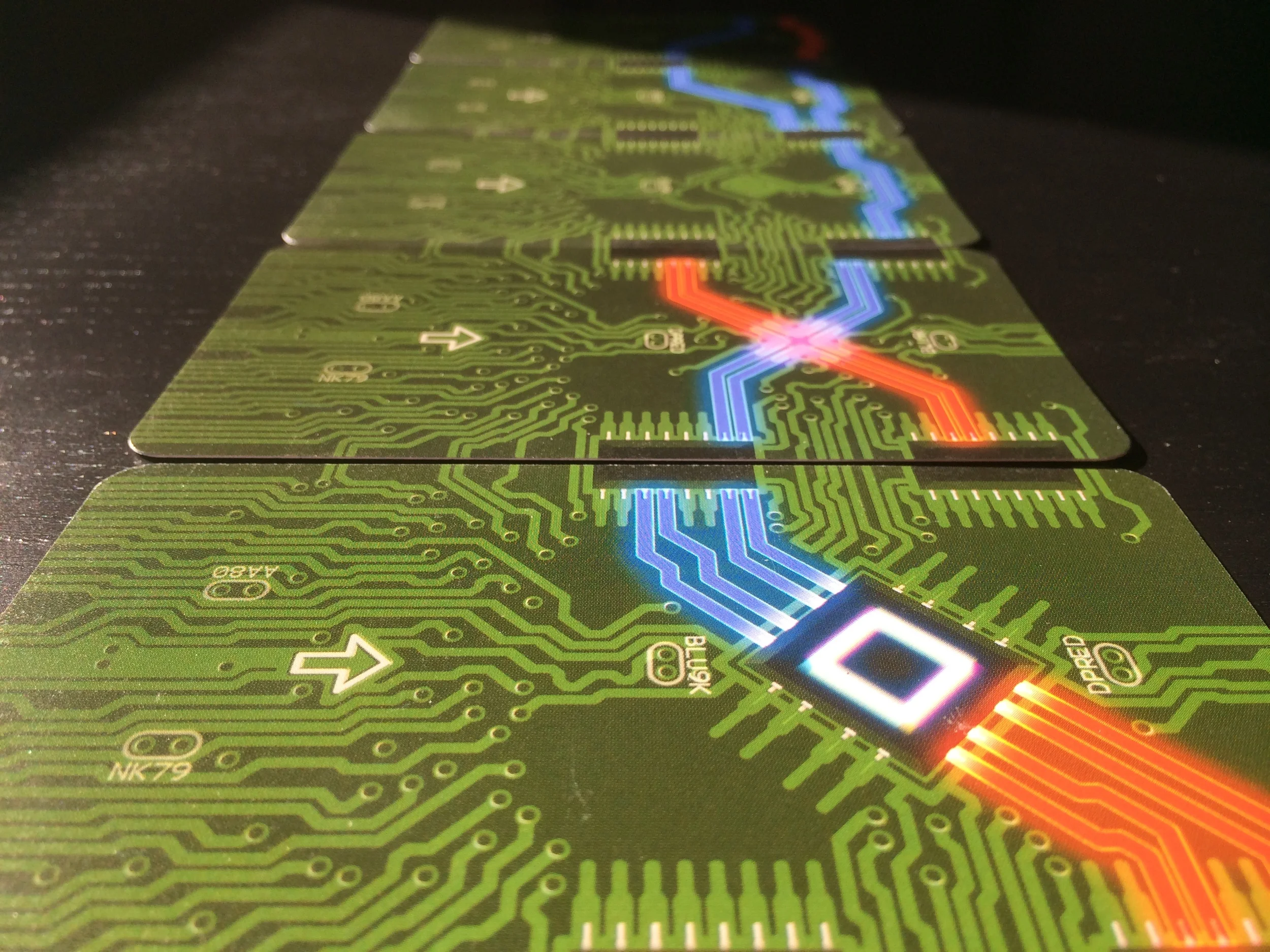

The double-sided cards in RESISTOR_ restrict information to one player or the other, while giving each player more information overall than they'd get from single-sided cards. What role does information play in the game, and how did you decide to parcel it out to the players?

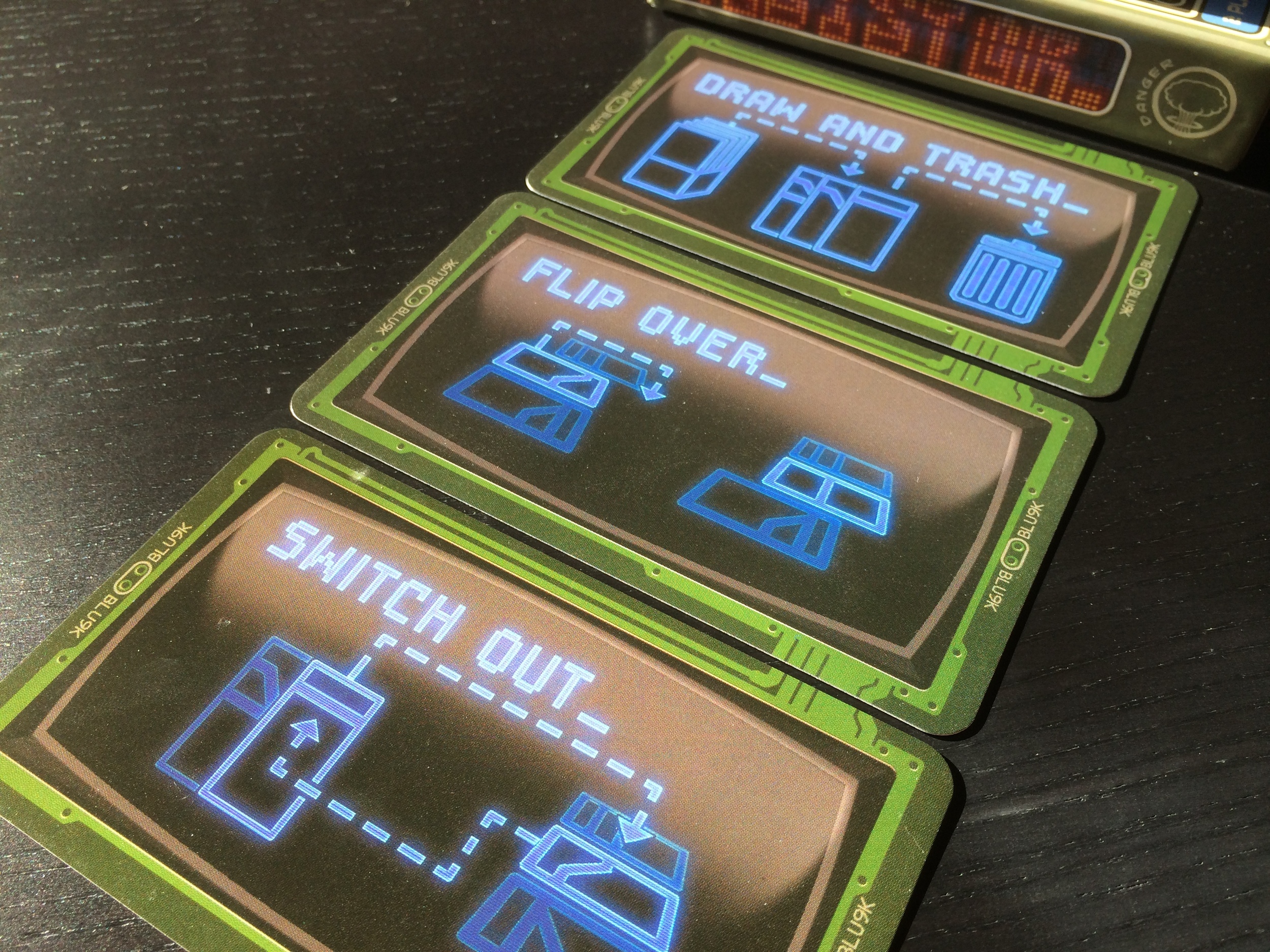

Information gain is important in RESISTOR_. We tried to tie the times you gain information mostly to when it's not your turn, so it was a way for us to reward the inactive player for paying attention--or lose an advantage. It's also important in how the cards in hand work. We could have just had each player hold four one-sided cards, but because the cards are double-sided, when a player takes a card for themselves or uses it, they're taking an unknown card away from their opponent. This reinforces that both the board state and your choices available are constantly changing. It also adds an interesting psychological dynamic to the game. Because you're holding two cards, you think of those cards as "your" cards, and the cards in your opponent's hand as "their" cards, when in reality, you're just sharing those four cards. So when a player does the Draw and Trash action, they often say, "I don't want to give you this card, so I'll trash a card from my hand." Even though the information is very clear, physically holding onto that information changes the way players look at it and treat it.

Are there any lessons here that can be useful to designers when figuring out the right mix of public versus private information in their game?

The right mix of public versus private information really depends on the kind of game being created. If you're making a cooperative game, there's not a lot of reason to have an excess of private information unless you want to constrain the players' ability to communicate.

But in a game like RESISTOR_, the top faces of the board and both sides of every card in the discard pile are the only public information, because so much of your turn relies on that hidden information. Also, the use of private information really reinforces soft gotcha mechanics, since you might be sitting on something that can really change the game. How information is delivered, for us, was highly tied to the physical manipulation of the pieces, and we thought that this was a explorable area.

Thinking about the game as a physical thing can be a very informative angle to look at problems as well as look to your greater game design. Jaipur does this very elegantly with how it handles the camels. You could hold those in your hand, but that would be awkward, and so they made a choice for you to put them face up in front of you. This idea messes with public and private information and also speaks to what the players are physically doing at the table. Another good example is Sheriff of Nottingham--the bags aren't necessary, but the action of the sheriff physically taking the bags and threatening to open them once they're out of the players' hands adds so much to the feeling of it.

The Resistor cards shake up the game in several ways, including by shortening the circuit required to hit your opponent. This pushes the game toward a resolution and gives it an arc. How did you decide what effects the Resistor cards would have in the game?

Before the Resistor card was in the game, we had many problems we needed to solve, but we knew that we needed to keep the game short and simple for our audience at the time we created it. We had to solve as many problems as we could with as few mechanics as possible. Because each player has three actions afforded to them each turn, one player could continuously undo what the other player had done, which made the game feel stale, and often ended in victory for the first player who scored. The Resistor stops this from happening because it has the potential to change more on the board than you could with your normal actions, but due to its chaotic effects, it adds in a risk/reward dynamic.

We also felt that adding in the healing element helped to balance it as well, not only because it can help a player gain footing, but also because the player who got healed then discards their hand and draws a new hand, which burns through the deck quickly. The Resistor card is more likely to punish the person with the most advantageous situation at the moment, because if you are fully connected across the board, you are more likely to be affected.

In conjunction with the Draw and Trash action, the Resistor adds in a mechanic where the game destroys itself. So it's dangerous to the person in the lead, helps the person who is losing, and shortens the game, which ends up upsetting the memory balance of the game, since some people have a hard time remembering the card faces. But it also adds risk, because using a Resistor has the potential to be chaotic, and could reveal more Resistors, which can shorten the board way more quickly--or end up unexpectedly flipping cards back over again.

All of this enhances the idea that you should use cards in the moment or expect to lose them, and also prevents players from counting or remembering cards, since they can be discarded before you see both sides of them.

How important is it for a short game to have a changing game state and arc, and what are some ways of achieving this in a short game?

This is important in both short and long games, especially those in which there's a chance you could be losing very early on and never have a way to catch up. Nothing is more demoralizing--or less fun--than a game where you feel like the loser left behind. In a shorter game, you might even be able to get away with less of this, since sometimes the change happens so abruptly that the game ends. But in a longer game, it's important because it's part of what keeps players engaged.

If a shorter game doesn't have an arc, then you want to ensure every playthrough experience is different in some way. Hive is an example where it's a short experience but there's a chance that it's going to be exactly the same, depending on strategies. Seven7s is the opposite: every time you play it, you're going to get to the ending in a completely different way. By that we mean, the end state is always changing, and the values of the cards change as you're playing. So you're constantly making choices about whether you think the value of the cards in your hand will go up or down, and whether or not they're worth keeping or using. There's also no guarantee about the length of the game--one player could feel they have a good hand and try to rush the ending, while another might slow it down to get better cards. But it's never entirely in your control.

RESISTOR_ is strictly a two-player game. Did you ever consider expanding it to handle more players?

Absolutely. We considered this often, but when it wasn't coming together quickly/easily, and it felt like we were really trying to force it, shoehorn it, it just didn't feel like it was natural or intuitive. Eventually, we hit a point at which we decided that our efforts would be better spent making it a really good two-player game than trying to make it an inferior four-player game. Of course, we still have ideas for a multiplayer version, but RESISTOR_ as it stands is a finished product. If we did revisit the four-player idea, it would likely be as a totally different game, or a sequel to the game. We have some cool ideas for it, though...

What are some special considerations for designing a strictly two-player game?

Generally, a two-player game should be shorter. Obviously, that isn't a hard rule or anything, but it feels like if you're making a long-form game, you're making it for more than two players.

With our game, because of the double-sided cards, the players must also literally face each other, which is interesting, because most games don't have any kind of physical requirement to optimally play them.

Also, in a two-player scenario, it's especially important to make sure that both players are engaged at all times, which is why we tried to make sure that all of the actions available to a player on their turn also in some way affect the other player, even if it's just that they're gaining information. When you're designing a game for more than two players, it's more understandable that there will be some down time. But given the length of a two-player game, players shouldn't have down time, and the tempo should be tight.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Richard Durham, Matthew O’Malley, Isaias Vallejo

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Luis Lara, Behrooz Shahriari, Aidan Short, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Robert Booth, Doug Levandowski, Aaron Lim, Nathan Miller, Marcel Perro, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Kevin Brusky, Kiva Fecteau, Scott Gottreu, Michael Gray, JR Honeycutt, Scott Martel Jr., Marcus Ross, Diane Sauer, Steven Tu