The Process: Dark Moon: Shadow Corporation by Evan Derrick

/In The Process, board game designers walk us through the process of creating their game from start to finish, and how following their path can help others along theirs.

In this installment, Evan Derrick describes how he created the Shadow Corporation expansion to Dark Moon.

Process

I made a happy discovery when I began designing Dark Moon: Shadow Corporation: Expansions are so much easier to design. The core system was set in stone and had been proven to be successful, so I simply needed to iterate on top of it. I immediately discovered why designers like Alan Moon and Donald X. Vaccarino put out a seemingly endless stream of expansions for their popular designs. When the development time is as much as 80% less than creating a new game from scratch, it’s not hard to see the appeal of creating five expansions in the time it takes to design one new game.

I had two central design goals when I designed Dark Moon. The first was to create a similar experience to its spiritual big brother, Battlestar Galactica, but in a third of the playtime, and the second was to ratchet up the paranoia and mistrust between players as quickly and intensely as possible. When I sat down to design DM:SC, I didn’t just want to preserve those two goals, I wanted to improve upon them. To that end, DM:SC both shortens the playtime without sacrificing any of the gameplay as well as amplifies the mistrust that players experience. If you experienced a lot of finger-pointing during games of Dark Moon, be prepared to point twice as many fingers when you add in DM:SC.

The Takeaway: Expansions are simpler to design since you’ve already done the hard work of building the foundation.

Theory

I’ll let you in on a little secret: I hate that Infected players can publicly “reveal” themselves in Dark Moon. In my designer heart of hearts I never wanted to give players that option. The fun of the game comes from the paranoia and mistrust which, let’s be honest, pretty much evaporates when all of the Infected players have publicly revealed. “If you’re Infected and you played poorly and the other players quarantined you and took you out of the game, too bad! Play better next time!” That was never going to work, however. If a new player (especially one that wasn’t great at lying) was dealt an Infected card, it wouldn’t be much fun for them if they were chucked into quarantine 10 minutes into the game simply because they didn’t have a convincing poker face.

Unfortunately, this means that some Infected players jump the gun and reveal themselves early when they really shouldn’t. Those shiny Infected actions are just too tempting! And the players don’t realize I included those in the game as a release valve, not as a viable strategy (and why should they?).

So for DM:SC I wanted to correct that behavior, which led to the evacuation ship.

Thematically, the evil corporation Naguchi-Masaki has heard about the pathogen spreading across their mining colony and they want a sample of it for their weapons division. They have “helpfully” sent an evacuation ship to Titan hoping that an Infected miner will get on board. The ship, however, has a limited number of seats, so only a few players can actually get on.

Mechanically, players can vote one another on and off the ship, and once it’s full they can vote for the ship to take off. As soon as the evacuation ship takes off, the game immediately ends and players check the status cards of everyone who was on the ship. If everyone on the ship is Uninfected, the Uninfected team wins, but if a single Infected player managed to sneak onto the ship then the Infected team wins. This means that Infected players cannot reveal themselves early, since it would be simple for the Uninfected team to use their voting power to load themselves onto the ship and take off.

The evacuation ship is easily the proudest I’ve ever been of a design mechanism. It accomplished all of my design goals in one fell swoop:

Shorter playtime: Since the game ends as soon as the ship takes off, sessions can be even shorter now without sacrificing any of the fun. Ending the game early and watching each player that was on the ship slowly flip over their status card is an amazing climax to the game.

More paranoia: If you thought it was easy to point fingers in Dark Moon before, wait until people start voting one another onto the evacuation ship! It easily adds paranoia on top of paranoia.

De-incentivize early Infected reveals: Infected players are incentivized to stay hidden as long as possible now. Publicly revealing themselves isn’t a path to victory now, but to defeat, as the Uninfected team will just hop on the ship and take off.

The Takeaway: Highlight what worked best with the original game and make sure the expansion doesn’t do away with the game’s strengths. Instead, make sure the expansion amplifies the original game’s strengths.

Theory Part 2

When I started designing DM:SC, the evacuation ship wasn’t necessarily the centerpiece of the expansion (which it is now). I threw in the kitchen sink of things I had discarded for the original game but had always wanted.

The first was a brand new team called the Company Man. If you receive the Company Man Status card, you’re playing to win all by yourself (it was inspired by the Tanner role from One Night Ultimate Werewolf). Unlike the other teams, surviving isn’t part of your win condition. Instead, your goal is to collect a sample of the pathogen and send it back to the company, no matter what the cost.

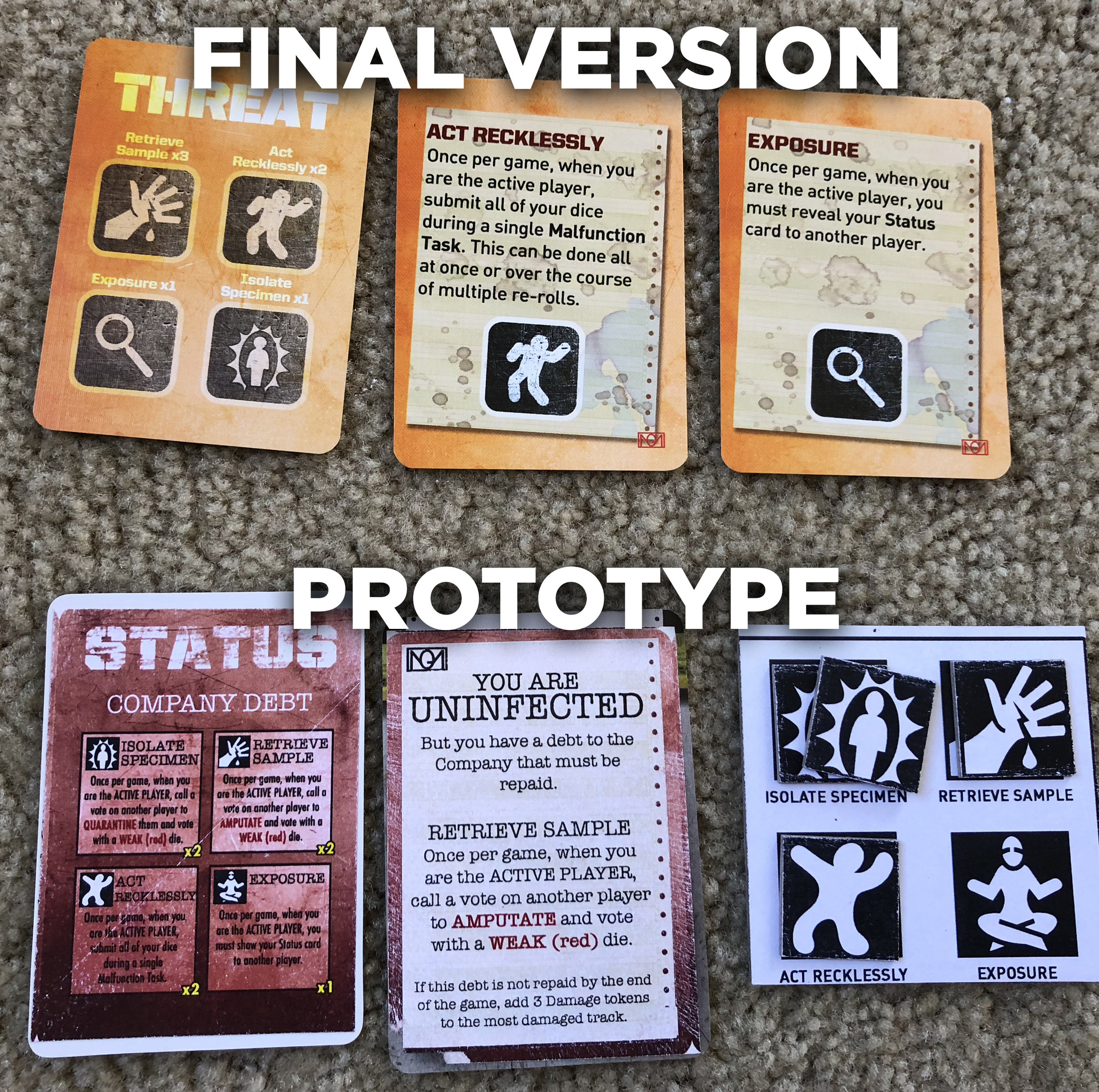

The second were blackmail cards (which eventually became Threat cards in the final version), a mechanism that had been floating around since the very first version of Dark Moon. Every player is dealt one of these cards at the beginning of the game, each card has specific instructions that that player must follow, and each instruction is for the player to do something incredibly suspicious. Thematically, the company is blackmailing the players to do something horrible (throw other players in quarantine, recklessly throw in all their dice on a skill check, etc.). Mechanically, this forces Uninfected players to act even more suspicious (the consequences for NOT performing the action on your card are much, much worse) and gives the Infected players an opportunity to act.

The main problem with both of these mechanisms is that they’re fairly complex. They require all of the players at the table to have a really strong grasp of the game and how it works and can be disastrous for new players. Misreading your Threat card or failing to understand the Company Man’s victory conditions can throw a wrench into the entire machine. Both add some fascinating tension to the game but they also ask a lot of the players.

Even for an expansion it felt like too much. The evacuation ship, the Company Man, and the Threat cards ratcheted up the learning curve significantly, even for experienced Dark Moon players. I was loathe to get rid of anything, however. Which is when Stephen Buonocore, the president of Stronghold Games and publisher of Dark Moon, made a simple yet brilliant suggestion: “Why don’t we just make them optional modules?”

Boom. That solved everything. The core of DM:SC is the evacuation ship and is included in every game, but the Company Man and Threat cards are now optional modules that you can add to the game if you want to. This allows players to get a good grasp of the expansion and its new rules at their own pace. Fearless groups can throw everything together for their first game, while most will introduce the modules slowly.

The Takeaway: Take particularly complex mechanisms and label them “modules,” thereby encouraging players to introduce them slowly rather than all at once.

Playtesting

The playtesting process for this expansion was so much easier than playtesting a new design. Whereas Dark Moon took 2-3 years of consistent development and playtesting, DM:SC was done in only a few months. Rather than make sure an entire game works from start to finish, you’re simply testing to make sure that the expansion doesn’t radically break the original design. Additionally, you have a built-in audience that is fairly eager to try out all of the new stuff you’ve created, making it that much simpler to gather playtesters.

From an emotional standpoint, playtesting a new design can be a fairly grueling process. You have high hopes that this version is the one that’s really going to work, only to watch it crash and burn in the ashes of your shattered dreams. But with an expansion you figure out what works and what doesn’t fairly quickly. You have the context of the original game to work within and that makes the design process substantially easier.

The Takeaway: Playtesting an expansion is much easier to do, given that you have a built-in audience as well as a successful design.

About

Evan Derrick is the designer of Dark Moon, Dark Moon: Shadow Corporation, and the upcoming Detective: City of Angels. He is the Creative Director for Van Ryder Games and oversees the art direction for all of their titles. He also has no free time, although he recognizes that’s really his own fault. You can email him at evan@vanrydergames.com or find him on Twitter at @evanderrick.

Cardboard Edison is supported by our patrons on Patreon.

ADVISERS: 421 Creations, Peter C. Hayward, Aaron Vanderbeek

SENIOR INVENTORS: Steven Cole, John du Bois, Chris and Kathy Keane (The Drs. Keane), Joshua J. Mills, Marcel Perro, Behrooz Shahriari, Shoot Again Games

JUNIOR INVENTORS: Ryan Abrams, Joshua Buergel, Luis Lara, Aidan Short, Jay Treat

ASSOCIATES: Robert Booth, Stephen B Davies, Scot Duvall, Doug Levandowski, Aaron Lim, Nathan Miller, Anthony Ortega, Mike Sette, Kasper Esven Skovgaard, Isaias Vallejo, Matt Wolfe

APPRENTICES: Darren Broad, Kiva Fecteau, Scott Gottreu, Nicole Kline, Scott Martel Jr., James Meyers, The Nerd Nighters, Neil Roberts, Marcus Ross, Sean Rumble, VickieGames